Yes, Virginia, There is a Renaissance. And Probably, A Middle Ages Too

Do you even periodize bro

When I was still in graduate school (shudders), we used to make fun of what we called “textbook history.” You know, the kind of thing you get in those terrible textbooks you were forced to read in high school and first year American history surveys at your local state college. The kind that went “and the this happened, and things changed and another era began, and then another…” These were basically poorly written chronicles meant to give your average students a bare timeline of events they could memorize, and we—enlightened True Historians™—looked down our noses at these people, because we were more sophisticated, we knew the world was soooooooo much more complicated and complex than these types of textbooks made it seem, blah blah blah.

All of which is essentially true, but we didn’t say those things because we knew what we were talking about. We said those things because we deeply insecure, without degrees or jobs, scarcely “learned” in any meaningful sense and desperate for our advisors and elders in the profession to take us seriously. And in lieu of actually achieving any of those things, we did what all flesh does: find a convenient scapegoat we could safely shit on, to console ourselves that, however pathetic we may feel, at least we are not like those people.

These reflections are prompted by an article which my friend Peter Kwasniewski shared the other day on the subject. The author is more concerned with how the Christian Middle Ages gave way to the ““post-modern” abyss” than I am, but sees it as beginning in some respects with the “Renaissance.” The title of his post references the skepticism of academic historians who have gone so far as to claim that “The Renaissance” is a myth.

The author wants to argue for the reality of “The Renaissance” as a starting point for the fall away from Christian civilization, while academic historians stress the essential continuity of “The Renaissance” with what preceded and succeeded it. Who shall decide, when doctors disagree?

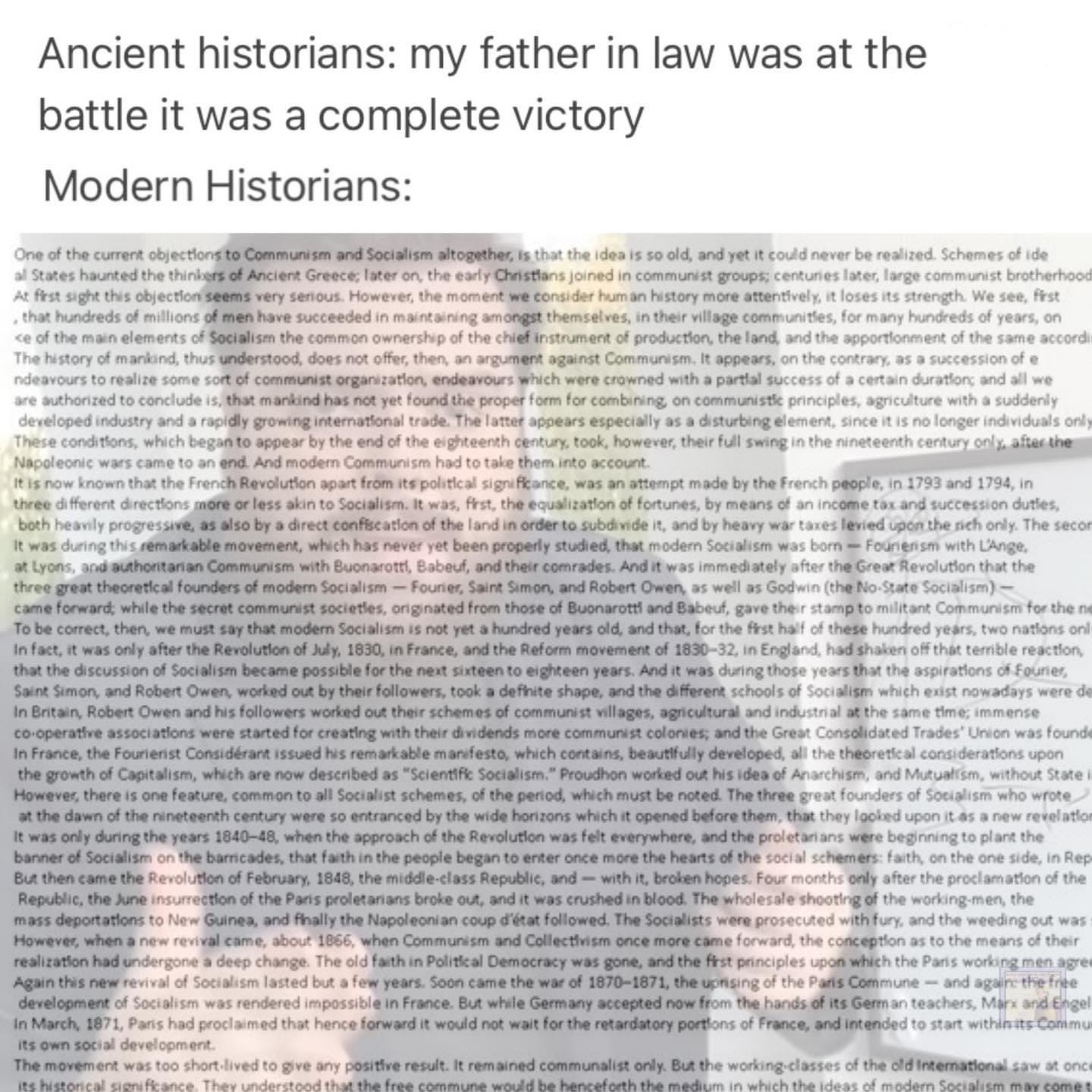

It helps to know (and yes, this is the kind of thing we studied in graduate school—your tax dollars at work!) the history of how historians came to view period from 1300-1600 (or 1700) as “The Renaissance.” The idea started out as humanist propaganda, with the Florentine poet Petrarch (1305-1374), who referred to European civilization of his day—you know, the one we usually call “the Renaissance”—as a “dark age.” He meant that is had fallen off from the ancient, classical civilization of Greece and Rome. In the early fifteenth century, the Florentine historian Leonardo Bruni first used a tripartite scheme of antiquity—middle ages—modernity to describe history, and thought of his own day as a having revived civilization. This scheme was picked up by later Florentine historians such as Flavio Biondi, though many such as Machiavelli, still wrote and thought of history in cyclical terms.

In the sixteenth century, this distinction between a “dark age” or “middle age” from a recent revival of civilization received a further boost from Gigorio Vasari’s Lives of the Artists, which portrayed the glories of Michelangelo and company as having rescued Italy from the “Gothic” barbarism of their predecessors. In the late sixteenth century, French jurists, using humanist methods of textual criticism, made the discovery that something called “feudal law” had supplanted Roman law during the “middle ages” (these were the days of the Wars of Religion, when in chaos of events the sinews of absolute monarchy were being worked out, legally and otherwise). In the late seventeenth century, a German historian named Christoph Cellarius penned a Universal History (1683) which was much translated and popularized the ancient-medieval-modern scheme after his death in 1709. Ever since, it has been the preferred way of distinguishing periods of history (with some modifications, of course: the invention of “early modern” history—my area of concentration—chief among them).

Enlightenment historians like Voltaire popularized this linear scheme almost as a dogma, that history moves “forward,” each period of history being thoroughly clear and distinct from that which preceded it, almost being hermetically sealed off from every other. (I recently heard the very fine Tudor historian David Starkey remark that you have to “understand history backwards” because it only moves “forward.”) Historians in the 19th century, following in the wake of the French and other great revolutions, naturally wanted to know how “their” era—the modern era of secular nation states—began.

Seek and you shall find! These historians—and they were great historians—found the origin point in “the Renaissance” of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. This term, with it suggestions of a singular beginning and break with the recent past of the “medieval” period is a coinage of 19th century historians such as the French republican historian Jules Michelet (1798-1874). The historian most associated with this idea is Jakob Burckhardt (1818-1897), the great Swiss historian who published The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy in 1860. Burckhardt especially associated the Italian renaissance with the emergence of the “individual,” as well as with the emergence of the self-consciously created state (lo stato), or as he calls it, “the state as a work of art.”

In the twentieth century, however, historians turned against this conception. Following the lead of historians such as John Huizinga, they began to question the equation of humanist learning with cultural rebirth. Huizinga, in his study of the Burgundian court, saw its culture as regressive and decadent, suffering from an unrealistic nostalgia for classical civilization. Latin ceased developing as a living language in the hands of humanists, while their obsession with on language and rhetoric bordered on the magical. Economic historians have noted that the period witnessed a severe economic downturn from its heights in the High Middle Ages, while some such as Lynn Thorndike thought the Renaissance obsession with magic and hermeticism retarded the progress of scientific endeavor.

In short, the “Renaissance” might not have been the golden age its publicists made it out to be, and historians looking for the origins of “modernity” began looking elsewhere. And if you look more closely at the experience ordinary people during that era (insofar as we have evidence for this), it is not clear how much actual difference there is between the mentality of someone in 1200 versus, say, 1550. In time, historians have designated other earlier eras that might have seen a “rebirth,” such as the “Carolingian Renaissance” or “The Renaissance of the Twelfth Century.” (The term has become ubiquitous of course and therefore deflates its currency; the naming of this or that era as a “renaissance” almost seems like an Oprah Winfrey parody at times—you get a renaissance! And you get a renaissance!) This is why some historians doubt the existence of “The Renaissance” as a distinct historical era.

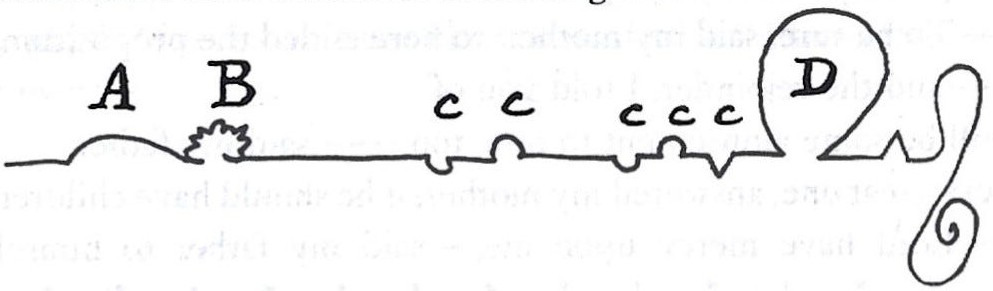

So was there a “Renaissance”? Well, one might start by questioning the idea that history moves “forward” and that every period has to be totally different from every other. You could even reject the “linear” idea of history altogether and adopt a cyclical view of history. But this hardly solves the problem. For every civilization, some times and places are going to be more important than others. There are things about fourteenth and fifteenth century Italy that make it unique and different, and things that are pretty much the same as what proceeded and followed that span of time. History is complicated. That’s why whatever type of historical framework you choose to work with, it’s best to think of it as a model that approximates a reality that is simply too complex to capture completely. My concept of history is neither linear nor cyclical but more like that of Tristram Shandy:

However, you still need a “shorthand” to refer to important events in a shared understanding of how things came to be the way they are. The author of the post I refer to above sees the Renaissance as the beginning of a falling away from Christian civilization, while historians like Burckhardt saw it as the beginning of the modern. There’s some truth to both. You can acknowledge the importance of that era (even if for different reasons) without agreeing upon everything concerning it, or buying into the myth of its absolute uniqueness.

In other words, there is nothing wrong with “textbook” history, and, yes, there is “a” Renaissance.

Thank you for coming to my TEDx Talk.