I was thirteen years old in 1991, and my parents took the family on a trip to Cape San Blas, a private beach in the Panhandle area of Florida. We spent a week there if memory serves, at rented beach house, enjoying warm Gulf waters and relaxing. The beach house had not TV or anything, but we didn’t care. We were there to swim and chill on the beach.

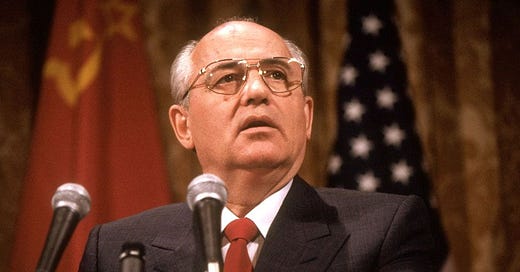

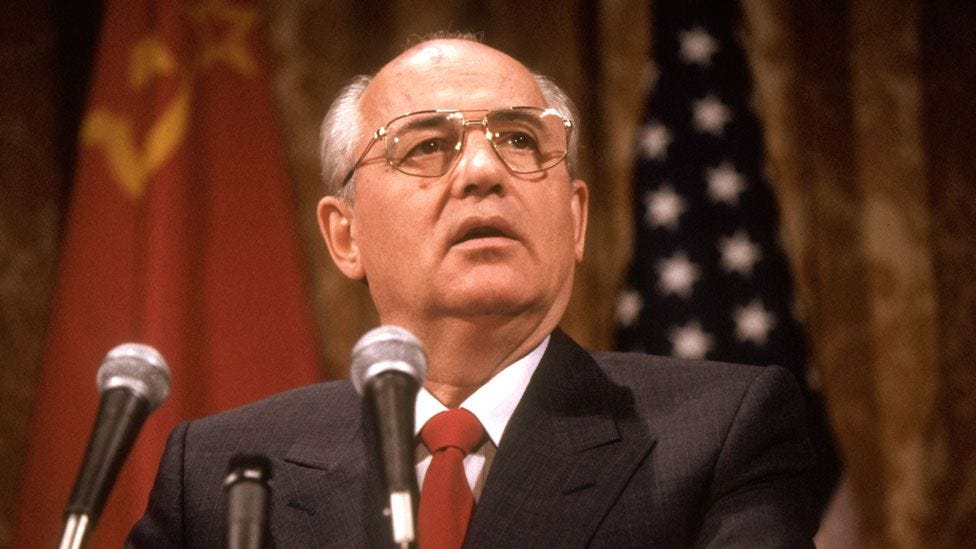

But we did have a radio, and during the last day or two (I think), we heard a disturbing new story: military officials in the Soviet Union had started a coup and detained Mikhail Gorbachev at his dachau outside of Moscow. We listened through the grainy, garbled radio broadcasts as best as we could, but it seemed ominous to my thirteen year old self. The Berlin Wall had collapsed less than years before, and the Cold War, with its threat of nuclear annhilation seemed over, but now it seemed some of hard linen commies were trying to turn back the clock.

I recall watching the dramatic events of the next weeks, when tanks surrounded the Russian parliament building, and Boris Yeltsin made his speech that launched him to the Russian presidency, all live on CNN. Within a few days, the tanks withdrew, and the hardliners backed down. By December, Gorbachev was gone, and the Soviet Union with him.

News of Gorbachev’s passing brought these memories back to life for me, and reminded me how old I am. 1991 was more than three decades ago—it’s almost impossible to comprehend. Born in 1978, I am not really a child of the Cold War so much as its dissolution. When the Berlin Wall came down, I saved the local newspapers for that day, because I knew what an important event it was (I’ve since lost them, alas). I was eleven, and already interested in history.

Needless to say, things didn’t work out the way that Gorbachev planned. Rod Dreher over at The American Conservative seems to think he deserves the lion’s share of credit for ending the Cold War, but I’m not so sure. It is true, world leaders like Gorbachev, Reagan, Thatcher, helped speed the USSR’s demise. But the people who deserve the most credit are those who helped undermine the legitimacy of communism from within, men like Lech Walesa and Vaclav Havel, the workers of Solidarity, even exiles like Solzhenitsyn, who kept the pressure and helped call attention to the mirage on which these regimes were founded. Of course these men needed outside influence to succeed, but theirs was the most dangerous and therefore worthy part, in my opinion.

Moreover, Gorbachev’s contribution to the end of the Soviet Union was mostly due to his incompetence, rather than any great insight as a statesman. Gorbachev thought opening up the Soviet Union would help communism, not hurt it. Americans tend to forget this or ignore it, seeing in his actions someone who had seen the light and accepted the American system was superior. But that’s not quite right. He thought he could combine the openness of the democratic countries he visited in Western Europe with Soviet socialism, not understanding this openness rested on a bedrock of habits, customs and institutions that were wildly at variance with the Russian experience and hardly sustainable in a system like the Soviet Union. His failure to understand this lead to the USSR’s collapse.

The most important contribution Gorbachev made to ending the Cold War and communism was not any positive step that he took, but rather the step he did not take. When protests sprang up in East Germany in 1989, the East German leader, Eric Honecker, asked Gorbachev to send Soviet troops to help quell the protests. This could have worked: it worked the previous summer in Tiananmen Square in Beijing, for example. But Gorbachev, convinced such coercion only turned people away from communism, refused. Honecker resigned, the wall came down, and a year later Germany was one country again. For that, at least, one can be greatful to Gorbachev, that he “could have done evil things but did not.”

As Dreher mentions in his post, Russians see Gorbacheve rather differently. To them, Gorbachev is the man who led to the loss of his country’s status and prestige, preparing the way for a decade of humiliation at the hands of unscrupulous oligarchs and Western bureaucrats. Not only did he open Russia up to horrible levels of corruption, he accepted at face value American diplomats’ assertion that they had no intention of expanding NATO after the Cold War. Instead, the American government almost immediately treated the Russians (even before the USSR dissolved) as a defeated third rate power whose opinions they need no longer take seriously. The Russians learned this lesson during the Serbian War in 1999, as Bill Clinton bombed Serbian Orthodox Churches to smithereens over the howls of Russian indignation at this brutal treatment of a Russian ally. Under Putin, the Russians have not forgotten this lesson, and though Putin is guilty of an unprovoked war of aggression in Ukraine, it is hard to deny that the situation could have been prevented had the US been more magnanimous to its erstwhile adversary in the 1990s.

Or, if Gorbachev had been the statesman Westerners seem to think he was. He was ultimately, I think, a decent man, unequal to the impossible task of making a utopian system work, while trying to change his country into something it had never been overnight. It would have taken a world historical figure to prevent Russia’s decline after the Cold War, and neither he nor his successor were such a figure. His decency should be not held in contempt, even as people share the cringe inducing commercials he made after the fall of the USSR or the riotously funny memes about them. That is the way he should remembered, I think: not for his greatness, but for the basic goodness and decency that made him too morally upright to sustain the immoral system he served.