There is a passage in Edmund Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France I’ve always liked. In it, he compares the French revolutionaries of 1790 (he wrote his work before it became really violent) unfavorably to those who had made earlier revolutions. Compared to the French revolutionaries, these men “had long views. They aimed at the rule, not the destruction, of their country. They were men of great civil and great military talents, and if the terror, the ornament of their age.” He goes on to mention specifically Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658), the English politician and general who became sole ruler of England during its “interregnum” when the monarchy was abolished (1649-1660). Of the great butcher of Ireland, Burke wrote he was “one of the great bad men of the old stamp.”

Burke used Cromwell and the whole idea of a nobler, more elevated brand of dictator to trash the French revolutionaries, whom he depicted as upstart country lawyers on the make. (He wasn’t wrong: lawyers made up a majority of the men in the National Assembly.) Burke was the first in a long line of thinkers, which includes Friedrich Nietzsche, who bemoan modern, “mass” society’s propensity to drown individual excellence in collective mediocrity. But it seems to me hit upon a rather crucial distinction in his polemic: that between “greatness” and “goodness.”

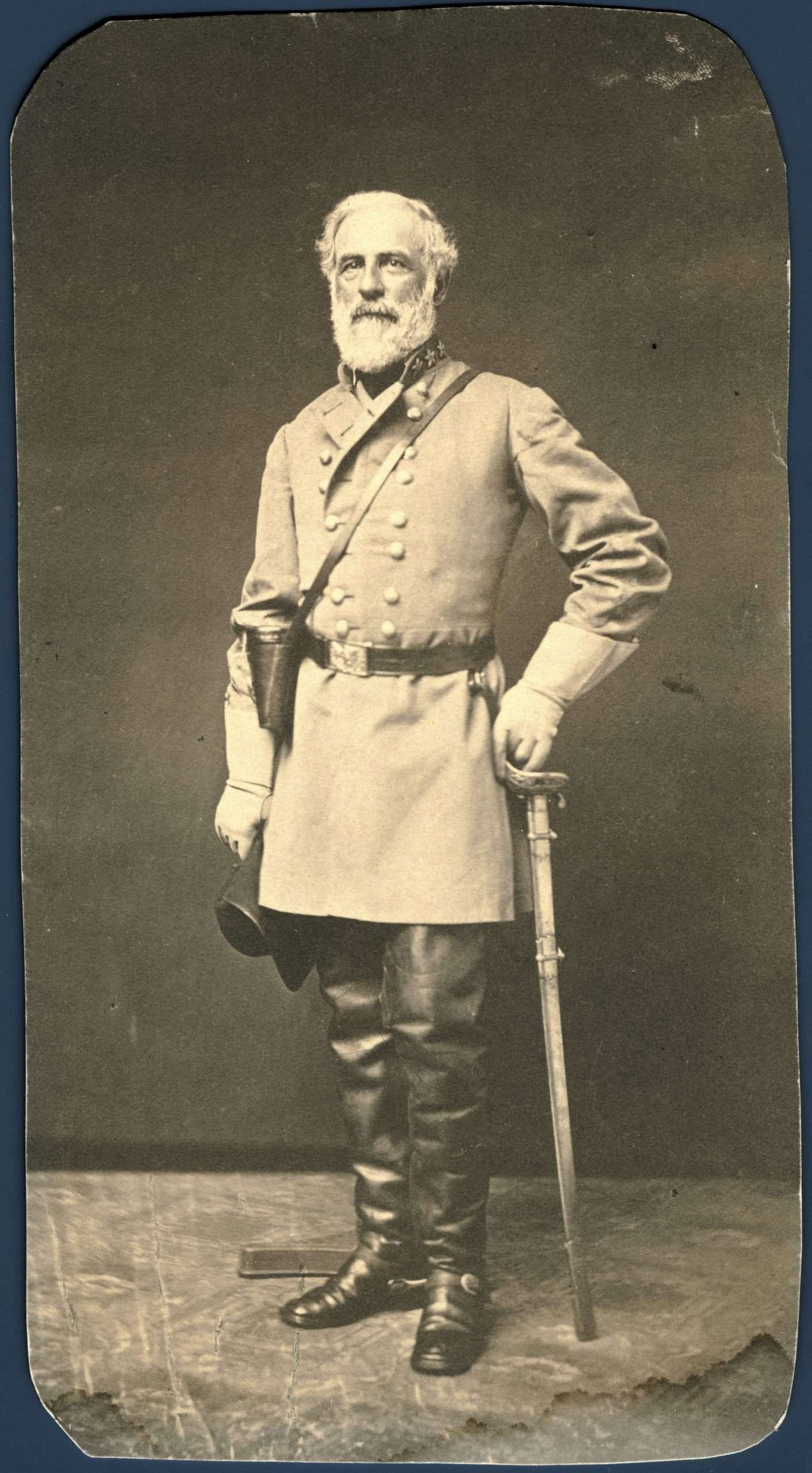

I am thinking of the whole issue of public monuments which has become so acute in this age of “wokeness.” The theory goes that because men like Robert E. Lee, George Washington, etc., are tainted by their association with slavery and therefore no longer fit objects of public veneration. They may have been great, but their moral failings make them untouchable, therefore, “anathema sit!”

The narrowness of this view ought to be apparent, but I suppose it is not. Wanting to acknowledge past wrongs is a noble instinct; the damning to oblivion of anything related to those sins is not. I made this point in an essay last year about our seeming inability to honor any personage if they depart one iota from current standards of morality.

It is a sign of decline in my view, that one cannot appreciate the virtues of someone, even if they are one’s enemy. I don’t myself think much of the “great man” theory of history as an explanation of events, but there can be little doubt some men impacted the world in ways that were unique and that demand respect. Of course, it is not as if one has to love or adulate men who are otherwise morally bankrupt. And Burke could not have imagined the scale of slaughter perpetrated by 20th century villains (I am not an apologist for the Hitlers, Stalins and Maos of the world). But it would be foolish not to recognize that the most wicked of men have talents. Otherwise, they would not have such an impact on history.

I’ve been trying think of “great bad men” and several obviously come to mind. The most obvious is Napoleon Bonaparte. That he was a tyrant I don’t think any can doubt, but it is rare the person that could deny his genius. One of the greatest generals and one of the greatest statesmen of world history, he seems to capture Burke’s sentiment: someone who, thought he brought war and ruin to much of Europe, he also rewrote the legal systems in most of Europe, with enduring effects. His trip to Egypt spurred interest in that country which led to the discovery of the Rosetta Stone and arguably the discipline of Egyptology itself. He spread ruin and warfare wherever he went, but one cannot deny his talents.

Another figure that might count as one of the great “bad men” of history is Otto Von Bismarck, the great chancellor and unifier of Germany. Bismarck was part of the Junker class, land owning estate Frederick the Great turned into a service nobility in the eighteenth century. Bismarck was the man who initiated the Kulturkampf, the attack on the German Catholic Church, imprisoning bishops and priests, seizing Church property, among other things, to curb the Church’s political power in Germany. He unified Germany behind Prussia and made it the greatest power on the continent, which of course paved the way for the horrible World Wars of the twentieth century.

But there is little denying his political genius. When he was called to Berlin to be the Chancellor of Prussia in 1862, Prussia was the least of the great powers. Few observers thought the various German states could be united into a single polity. Yet within a decade, Bismarck had fulfilled the dreams of German nationalists by using Prussian military power and astute diplomacy to best first Austria then France. Whatever one thinks of the effects of his achievements, it would be churlish to deny the man’s greatness.

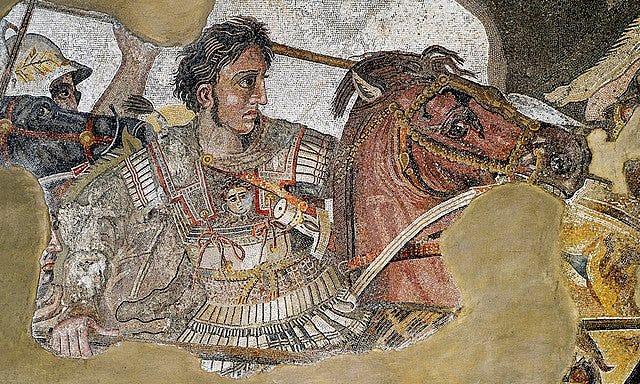

You could name many others, I should think; Alexander the Great comes to mind, actually. Plutarch’s portrayal of his character in his Lives makes him seem like a brute with a bad temper, but who would deny his accomplishments? I suppose Julius Caesar would fit the bill as well. A great general, statesman, but also a ruthless politician, though that description might still better fit his nephew Octavian, who brought the Roman Civil Wars to an end and turned Rome into an imperial capital while also (according to Suetonius) brought virgins to his palace to be deflowered and once sacrificed three hundred prisoners before a battle.

We are splitting hairs here, and one could some figures of history as good but flawed men, though I don’t know where you draw the line. And, rarely, there historical actors who are both good and great, but they are few. As to whether or not someone is “great” despite their being “bad,” this has more to do with one’s political view than anything else. I see Robert E. Lee as a good but flawed man but most people outside of Southerners seemed to view him as the evil incarnate because he owned slaves. My point, if I have one, is that greatness does not equate to goodness. I may be a good person and Robert E. Lee the Devil Himself, but when it comes greatness—the impact one has on history, society—he is worth a thousand of me, easily, and most people for that matter. Don’t misunderstand; in many ways it is better to lead a good if less consequential life. But that is no reason not to admire those who crimes mean they are not moral exemplars, but whose talents still command respect, even admiration.