My Middle Eastern Reading Binge: Part I

How I learned everything I wanted to know about Israel and Middle Eastern Wars but wish I hadn't

Fawwaz Traboulsi, A History of Modern Lebanon (Pluto Press, 2007) Augustus Richard Norton, Hezbollah: a Short History (Princeton UP, 2018) Ian J. Bickerton and Carla L. Klausner, A History of the Arab-Israeli Conflict* (Taylor & Francis, 2016) Ilan Pappe, The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine (OneWorld, 2006) A Very Short History of the Israeli-Palestine Conflict (OneWorld, 2024) Lobbying for Zionism on Both Sides of the Atlantic* (OneWorld, 2024) John J. Mearsheimer and Stephen M. Walt, The Israeli Lobby and U.S. Foreign Policy (Strauss, Farrar & Giroux, 2007) Ronen Bergman, Rise and Kill First: the Secret History of the Israeli Targeted Assassinations Program (Random House, 2018) Alistaire Crook, Conflicts Forum (Substack) *indicates I have not finished reading the book--yet

You might have noticed there is a conflict going on in the Middle East. Which one? you may well ask. Touché. I mean the war Israel has initiated with Iran.

I had been planning to give you an overview of some reading I had done on Middle Eastern conflicts, and thought now would be the opportune time. All the books listed above (as well as the one Substack) I would heartily recommend. Let’s dive in shall we?

Lebanon & Hezbollah

In the fall of 2024, Israel embarked a brief conflict with the Shiite militia Hezbollah, and this was the initial spur to my reading binge. I was interested because I have a deep respect for the Maronite Christians of that nation (Maronites are Eastern rite Christians in communion with the Pope of Rome). The conflict only lasted about a month, but I wanted to know more about how and why it started.

Fawwaz Trablousi’s book A History of Modern Lebanon is a dry, academic account of how the modern nation of Lebanon came to exist, from about the 1830s up to the early 21st century. If you are not aware, Lebanon was a kingdom in Biblical times but long ceased to be an independent state. But it retained (and still retains) a unique heritage, different from the predominant Arab countries in that region.

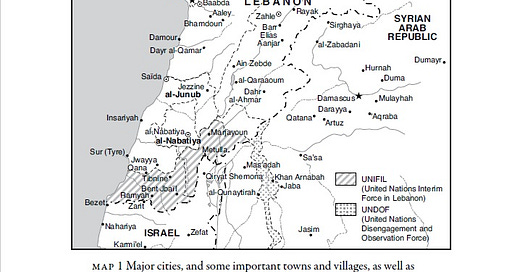

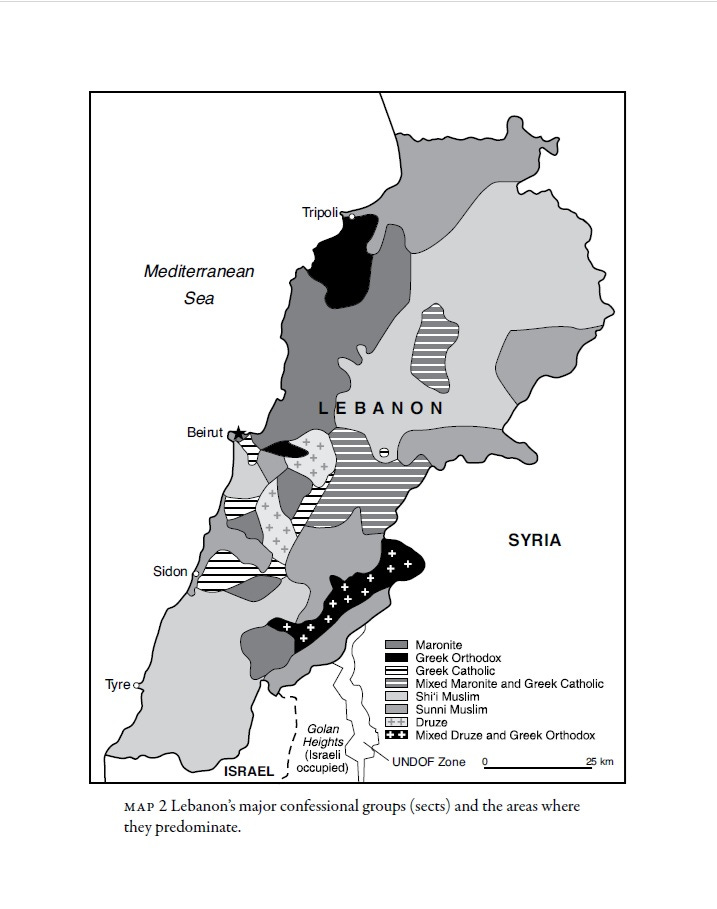

Trablousi’s book begins in the 1830s because that was when the Ottoman Empire, which ruled the Middle East, began to undertake reforms that benefited its religious minorities, at the behest of the European powers. This includes not only Maronites but Greek Orthodox, Melkite Catholic and Protestant Christians; Sunni and Shia Muslims; and Islamic offshoots such as Alawites and Druze, who are important in the region that would become Lebanon. (Indeed, it is one of the unique features of modern Lebanon that it has a sort of modernized version of the Ottoman “millet” system, where all the various religious confessions ae represented in government.)

Trablousi puts a good deal of emphasis on social and economic developments, both before and after independence in the region, and Lebanon’s important economic and cultural ties to the Syrian heartland. The book also details foreign interventions in Lebanese affairs, including for example the United States in the late 1950s. It covers the period up through the era of the Civil War (1975-1990).

Norton’s work on Hezbollah (“Party of God”), Hezbollah: a Short History, is a brief but fulsome account of that Shiite militia/shadow government in the 1970s, from the initial chaos of the civil war to around 2018 when the latest edition of the book was published. Hezbollah began life is Southern Lebanon, where the Shia population predominates, after the Israeli invasion and occupation of Lebanon in 1978. Members of what would become Hezbollah were responsible for the 1982 bombing of a U.S. Army barracks in Beirut, and the subsequent torture and death of the C.I.A. chief in Lebanon. In 1985, the founding members released a manifesto outlining their beliefs and aims, which explicitly drew on the Iranian Revolution and rejected Western beliefs.

Iran and Syria were the main backers of Hezbollah from its inception, and when the Israelis finally withdrew from Southern Lebanon in 2000, Hezbollah was largely seen as the most successful of the Shiite militias (there were others) who opposed the occupation. Their became a political force thereafter, effectively governing southern Lebanon, and in 2006 when the Israelis launched another war Hezbollah fought them to a standstill and they withdrew. This was Hezbollah’s high water mark and made the group a regional power. However, its involvement with the Syrian Civil War and the subsequent collapse of that regime has, for now, crippled its effectiveness, as Syria was its main backer but also allowed Iran to arm and supply it over land, which it cannot do through the air because of the Israelis. In the 2024, the Israelis assassinated most of the senior leadership as well. This may have ended its regional power, but it is still a major force in Lebanon despite these setbacks.

Norton’s book is a good short narrative for the history of the organization, but it gives a very thorough explanation of its beliefs (there is a chapter on ritual which is very interesting (my impression is that Shia Islam is much more comfortable with ritual than Sunni Islam) and worth the price of the book by itself.

What I Learned

As I noted above, my initial reason for this reading binge was my concern for the Maronite Christians of Lebanon. The Maronites have had close ties to both Rome and the French since the times of the Crusades. Once a majority in Lebanon, they have seen their numbers dwindle over the past century as the Islamic population has increased, as have Christians throughout the Middle East. But I did not understand how prominent the Maronites once were, or that they have been the aggressors from time to time (pretty much every sectarian group in the Middle East has slaughtered someone from another in recent memory).

What I found is just how complicated the history of Lebanon is. Trablousi in his book warns his readers at one point against seeing events in Lebanon solely through the lens of sectarian identity. At first, I thought he was protesting too much, but his book bears this out, and I suspect would for the whole Middle East as well. If you are not aware, Lebanon is a patchwork of different ethnic and religious groups, and under the Ottomans each had their own communities represented in what was called the “millet” system, which guaranteed them their place legally as subordinate communities in the empire. The French wanted to carve out a Christian state in the Middle East with the help of the Maronites in the nineteenth century, but nothing came of it. But when Lebanon became independent in the 1940s, its constitution guaranteed certain public offices to different religious groups (by law, the president must be a Maronite for example) effectively reproducing the millet system in a different form.

Despite all this, Trablousi makes clear how much social and economic factors matter in modern Lebanon. Tensions erupt between classes within sectarian groups, between urban and rural areas, and there are also family ties that can cut across other lines. All this is exacerbated by government corruption, which is rampant. Westerners tend to see events in the Middle East through a wholly sectarian lens, but part of what draws Arabs and others to Islamic movements is frustration with the corruption of secular governments, whose ideologies are secular. And there are plenty of them: nationalism, pan-Arabism, Marxism, Socialism, Baathism, they have all had a following in Lebanon and the Middle East, but none have proved as (relatively) successful as these sectarian movements.

Hezbollah is a good example of this. Because of sectarian nature of its constitution, the military of Lebanon is very weak, which is why so many militias flourish there. Hezbollah’s effectiveness at fighting the Israelis gained them the admiration even of some Lebanese Christians as result, and Hezbollah is as much of a national army as exists in that country. Lebanon is effectively a failed state at this point, and the collapse of Bashar al-Assad’s government in Syria (with the help of the US and Israel) doesn’t bode well for that country. What I have learned about it makes me think Hezbollah is far from dead, for that reason.

One last thing I learned is that events in Lebanon are inseparable from the broader Arab-Israeli conflict in the Middle East. The next installment on my reading binge will deal with the books on that never ending conflict.