Florida Travels: New Smyrna Beach (I)

An almost winter like day in the sun, in search of history and natural beauty

A few years ago, I made a list of the places I had never been to in my home state, both for historical and cultural reasons, that I wanted to visit, with the goal of visiting as many of them as possible. This past week I took my first trip to New Smyrna Beach, on the Atlantic coast of Florida, and what follows is a photo essay on my day spent there, broken up into two parts. Enjoy. -Darrick

When I awoke early on a Wednesday morning, it was bitterly cold, in the low 40s outside, even though it was late March. I planned my trip the evening before, so as to maximize my time, as this was only a day trip. I put on a pullover but made sure to bring a change of clothes, since the forecast saw things warming up quite early in the day. This was my spring break which, alas, is not as exciting as when you are student. Nevertheless, I was very eager to visit my destination, New Smyrna Beach Florida, as I had never been there before.

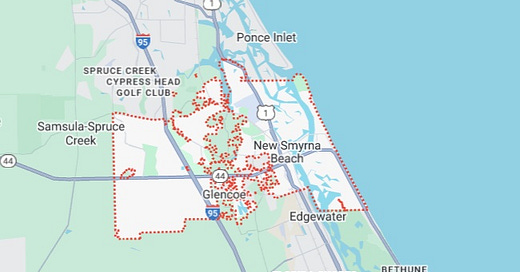

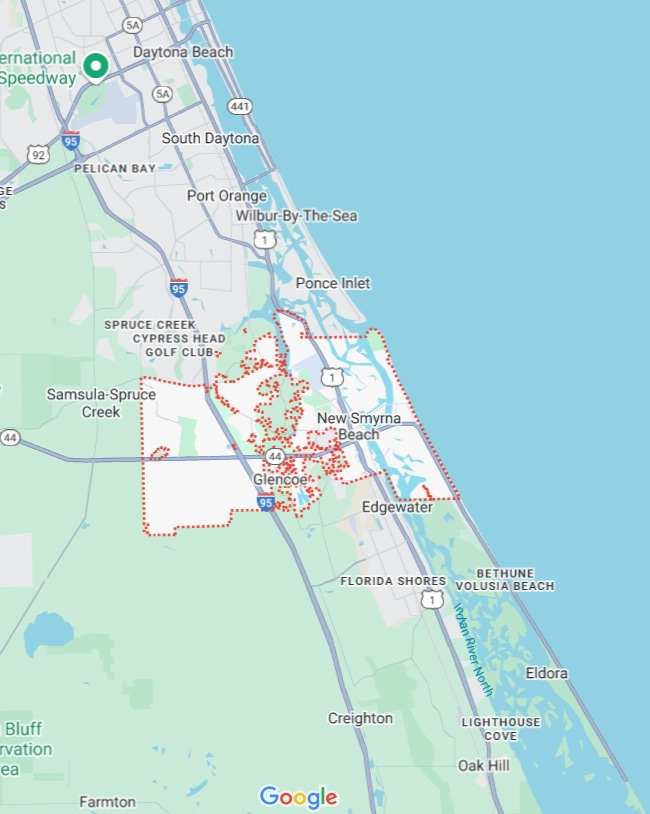

New Smyrna Beach sits on the Atlantic, just south of Daytona Beach (the more famous Spring Break destination) and just north of Cape Canaveral, where NASA launches its shuttles into space.

The town of around thirty-two thousand derives its name from a settlement planted there in 1768 by a Scotsman named Dr. Andrew Turnbull. Between the end of the Seven Years War in 1763 and the Treaty of Paris ending the American War of Independence in 1783, Britain controlled Florida, dividing it into two territories, East Florida (centered on St. Augustine) and West Florida (centered on Pensacola). Turnbull was the friend of the British governor of East Florida, James Grant, and in 1768 he founded a settlement sixty miles south. He dubbed it New Smyrna in honor of his wife, the daughter of a Greek merchant from the city of Smyrna, in the then Ottoman Empire. Turnbull attracted over 1300 mostly Greek, Italian and Minorcan settlers (Minorca is an island off the coast of Spain) to his new town. But despite a promising start, disease and Indian attacks undermined its stability and in 1776 several hundred surviving colonists removed to St. Augustine, where today many still boast of their Minorcan ancestry.

The foundations of Turnbull’s settlement still remain, forming part of a city park in New Smyrna Beach, and this was my first stop on arrival in town. I pulled into the parking lot in front just before 8:30am, when it was still quite cold. I saw several denizens of the town walking around in caps and coats as I parked my vehicle, and pulling a cap over my bald head, entered the park.

At the front park is a monument erected by the American Hellenic Progressive Education Association in 1968 to commemorate the arrival Greek settlers, the first on the east coast of North America.

As you can see in the photo below, Turnbull did not build his settlement on the ocean directly but on the Indian River, which runs parallel to the Atlantic. Not much remains of the actual buildings but the stone foundations, made of coquina, a local rock made of shell fragments.

If you wondered why I was so keen on seeing what’s left of Turbull’s fort, it is because of my background as a British historian. For most of my academic career I saw no real connection between what I was studying and my actual life, so finding any such connection always intrigues me. I had no idea when I was younger that Great Britain actually ruled the state I grew up in (or at least the territory itself), and so naturally piqued my interest. Not coincidentally, I am writing a novel set during this period of history, and Turnbull appears as a minor character in the story, so I wanted to see the place for myself, perhaps to gain some inspiration from it. I don’t think I really did, but it was interesting to see for myself the remains of Turnbull and his intrepid Mediterranean settlers’ project, especially as it rests on such a lovely spot.

It didn’t take long to reconnoiter the park, and I had some time before I made my next stop, so I took a walk along Canal Street, which is the center of New Smyrna’s “Historic District.” Not much was open before ten o’clock, but I enjoyed the brisk morning air, nonetheless.

I found a local coffee shop and hung out there for twenty minutes or so, journaling my thoughts, before starting the next part of my tour—Ponce Inlet, just north of New Smyrna Beach.

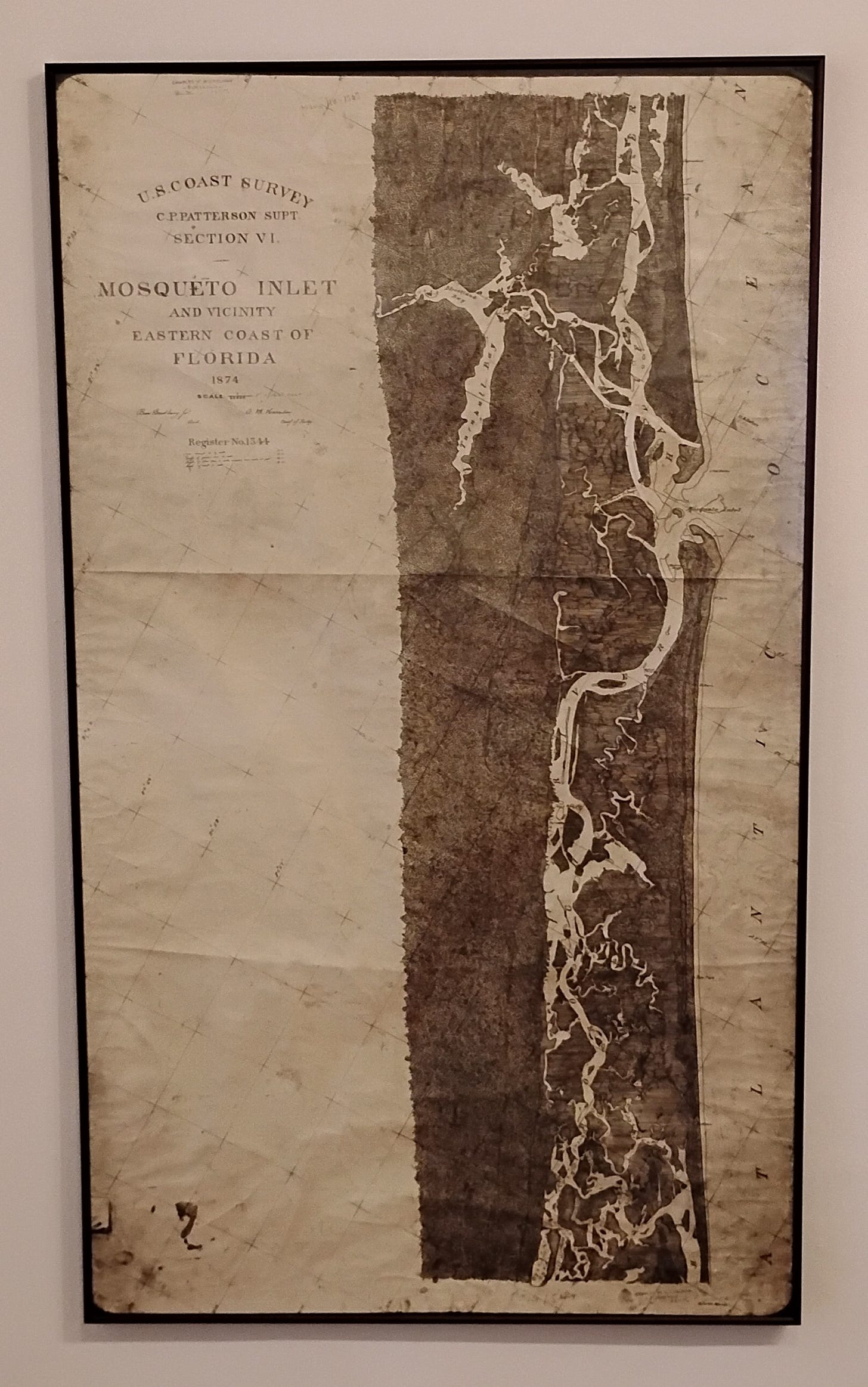

Ponce Inlet sits on the Atlantic Ocean, on a barrier island south of Daytona, between the Halifax river and the Atlantic. Settled in 1887, the town, which the inhabitants originally christened Mosquito Inlet, is home to over 3,300 people. However, in the 1920s, the residents of the town, wanting to attract tourism, thought a more appealing name would help, and settled on Ponce de Leon Inlet, after the Spanish Explorer, even though he likely never set foot in that area.

Besides being a lovely and picturesque seaside town, Ponce Inlet is mostly known (if only in Florida) for its lighthouse, the tallest in the state at 175 feet. The temperature was already in the sixties, and I stopped on my way there, pulling off to a side street that looked deserted and changed clothes in my car. Thus, wearing shorts and flip flops, I pulled into the parking lot at the lighthouse, which is no longer in use and is now a museum, a little after ten.

The museum is actually a complex of buildings, and not just the lighthouse. The home of the lighthouse attendant and other buildings are part of the complex. Across the street, an old hotel from the late nineteenth century is also a museum as well. Among the items on display there are a collection of lamps used in lighthouses through the years, as well as an anchor which “might” be from the 16th century, according to the sign accompanying it.

The lighthouse was in use from 1887 but there were lighthouses on the inlet long before this. In 1835, the federal government built a forty-five foot tower on the south side of the inlet, but due to poor management (oil for the lamps never arrived), the lighthouse never served its purpose. A storm undermined its foundations, and later in 1835, Seminole Indians attacked the lighthouse during the Second Seminole Indian War. The Seminole tried to light the lighthouse on fire but could find no oil to do so. A few weeks later during a battle, witnesses saw the leader of the raid on the lighthouse, a Seminole named Coacoochee, wearing lamp reflectors on his head as an ornament.

Aside from Seminole attacks, the builders placed lighthouse too close to the shore, and it collapsed into the sea in 1836. The government would build other lighthouses on the inlet, and by Confederate Blockade runners would use the inlet as a refuge during the Civil War. In 1862, the sent Union ships into the inlet to find the Confederate ships resulting in the deaths of the two commanding officers along with six seamen. Later on, ships going to and from Cuba used the lighthouse to navigate during the Spanish-American War. By the 1930s, the Coast Guard had taken over care of the lighthouse, and made its operation automated by the early 1950s. The Coast Guard decommissioned the lighthouse in 1970, but the townspeople bought the land and turned it into a museum open to the public in 1973.

Besides its role as a naval beacon, the lighthouse also forms part of a curious piece of literary history. In 1897, the author Stephen Crane, famous for his Civil War novel The Red Badge of Courage, enlisted as a seaman aboard a tugboat named The Commodore, which was running guns to the Cuban rebellion against Spanish rule. Crane was working as an undercover correspondent for the New York Post when the ship sank the morning after setting sail from Jacksonville, Florida, about 12 miles from Daytona Beach. Eight people died but survivors, including Crane, made their way to land by following the beacon of the Mosquito Inlet Lighthouse. Crane would later fictionalize his experience of survival in his short story, “The Open Boat.”

All this was music to my ears, learning of the Lighthouse’s connections to these types of historical events. I am always fascinated by the way seemingly inconsequential places or people are somehow connected to the larger dramas of the past. But the best reason to visit the lighthouse, of course, is the spectacular views its provides of the inlet and lagoon. The two hundred and thirty one steps to the top were not exactly a piece of cake, but the sight that awaits the traveler at the top are well worth it.

By the time I left Ponce Inlet, it was well past eleven o’clock. The sun had by now driven the temperature up, and turned it into a marvelous day. It was almost as perfect as a Southern California day (though not quite). The temperature peaked around seventy-three, and the humidity was much lower than normal, making it akin to a spring day in Florida, if such a season existed. As I headed south, I opened the sunroof of my CR-V and let the ocean breeze Next stop: Canaveral Shores.

The Canaveral National Seashore is a national park and is the “longest stretch of undeveloped Atlantic coastline in Florida” according to the National Park Service. Canaveral consists of some 58,000 acres of unspoiled land, mostly on the barrier island that sits between the Atlantic Ocean and the Mosquito Lagoon. I wasn’t there to walk on the beach, however, but to discover some traces of “Old Florida” in this relatively “pristine” setting.

As you head south from New Smyrna toward the park down A1A, the houses gradually disappear, with sand dunes and hammock taking their place. Entrance to the park without a seasonal pass is twenty-five dollars, which I did not know before going, and the toll booth does not accept cash (sign of the times, I guess). Still, my first stop lay close to the entrance.

The Turtle Mound Archeological Site is not much to look at—it is literally a big mound of earth whose shape looks vaguely like a turtle. But this formation is not natural, but the result of human habitation. The mound was created by the Timucuan people of Florida, between 800 and 1400 AD. I have a Timucuan Indian as a main character in the novel I am writing, which is another reason I wanted to visit Turtle Mound.

In these types of mounds, archeologists have found shells, bones and pottery, though they have not done a full excavation of Turtle Mound in order to preserve it. Many of these mounds were destroyed for landfill in the 19th century or else bulldozed to make way for railroad lines. Turtle Mound is the largest shell midden in the U.S., and stands about fifty feet high, though some believe it could have been as tall as seventy-five feet in the past. Spanish colonists and sailors used it as a landmark in times past as well.

The mound gives you a good view of the lagoon and some archeologists believed the Timucua may have used it as a refuge when hurricanes hit the area.

Human history comes in layers, even in Florida. I have always been fascinated with the way one civilization, one culture overlays another, especially in places like Europe. It is more impressive and visible there, “Old Florida” contains the same pattern, even if you have to know what to look for, just as the Timucuan fished, swam and plied their boats in the Indian River centuries ago, so do Americans today.

I didn’t have any real plans to stay longer at Canaveral, as it was not close to two o’clock and there were a few more places I wanted to visit before wrapping up the day. Still, I hopped in the SUV and drove a bit further, and found another piece of “Old Florida” history awaiting me.

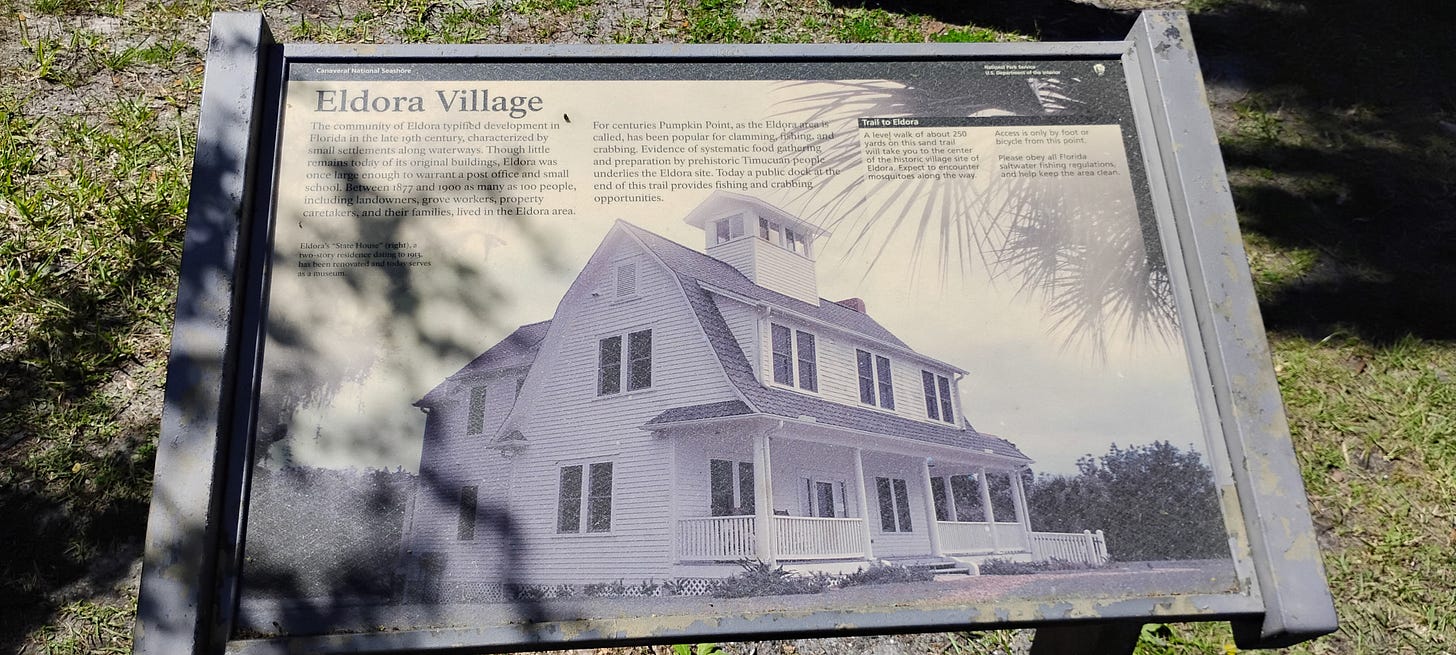

When I saw the sign marked “Eldora Road,” I suddenly remembered another stop I had wanted to make while in the area. The road wound through the hammock toward the Indian River before turning back toward the ocean and A1A, but brings you to a parking lot just as a dirt road begins, leading to the river. From there, you have to walk two hundred and fifty yards or ride a bike to your destination, unless you have a handicapped permit.

The Eldora State House, as it is called, is all that remains of the village of Eldora, founded in 1877 as a farming community on the Indian River. Freezes and competition from farms farther inland after the coming of the railroads doomed the farms of Eldora. In the early 1900s, wealthy northerners bought up the land of bankrupt farmers and turned it into a winter resort. The community at one point had a school and a post office. The Coast Guard also had a presence at Eldora as well, but when it moved to Ponce Inlet in the 1930s, the town all but ceased to exist except for a few houses like Eldora. The Eldora House had several owners since its construction in 1895, the last of whom died in 2000. Today, the house serves as a museum, but it is only open to visitors on special occasions. The last occupant, Doris “Doc” Leeper, was a sculptor and painter from New Smyrna Beach, who moved there in 1958. She became an environmental activist, and she was instrumental in the creation of the Canaveral National Seashore, and so the house is a fitting monument to her efforts.

When I lived in Kansas, I became aware of the phenomenon of “ghost towns,” small settlements whose inhabitants abandoned because they could not sustain themselves economically in the plains of the Midwest. It never occurred to me that such a phenomenon could exist in Florida, where all my life the population has been growing by leaps and bounds as millions of people moved here over the years, no more so than today when cars pack every major highway bumper to bumper. And Eldora suffered its fate partly for the same reason that some of those Kansas ghost towns did: the coming of the railroad. Whereas those Kansas towns usually died when the railroad didn’t come close enough to sustain them, the economic competition it brought doomed Eldora. One doesn’t normally think of John Flagler’s railroad (the northern magnate who built a railroad line from the Northeast down to Florida in the 1930s) as causing economic privation, but in this case it did. Of course, men like Flagler helped turn Florida into a resort destination, where people such as the inventor Thomas Edison, the automaker Henry Ford, former president Harry Truman, novelists Ernest Hemingway and Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, and the poet Wallace Steven, just to name a few. This was the prelude to Florida’s second founding, after World War II, when the invention of air conditioning and the mass migration to the Sun Belt of retirees reshaped it entirely. But here, on the shores of the Indian River, a little bit of the old world remains, however fleeting.

The sun had reached its zenith, and would begin to slowly fade into the west. I thought about driving farther into the park and taking a walk on the beach, but decided against it. Instead, I decided to leave and drive back up the shore and across the river, for two more stops on my historical tour of New Smyrna Beach.

The second part of this essay which concludes my expedition to New Smyrna Beach will appear in the next few days.-Darrick