Elvis the Lamb

Recently I watched the new Baz Luhrmann film Elvis, and enjoyed it more than I thought I would. I had never heard of Luhrmann before, though he is apparently known for directing films such as Moulin Rouge, which is probably why I had never heard of him. However, I thought Elvis was very well done cinematic terms, and I want to address that as well as some of the cultural cues that the film drops but never quite articulates.

The film begins with “Colonel” Tom Parker collapsing of a heart attack in his Las Vegas home, and the film is narrated by that character played by Tom Hanks. I found this puzzling in a way in which I will come to later, but on the surface it makes perfect sense. Luhrmann sees Parker as a seedy showman, and clearly is appalled at the way he manipulated Elvis. But he uses him to some effect, as the film isn’t so much a full on biography as an homage to Elvis the celebrity, Elvis the performer. Luhrmann’s visual style is one that is informed by popular culture, the screen being filled with montages of the Vegas strip and billboards one second, and by faux news footage the next quick succession. This crowded and somewhat over the top visual style irked me at first, but became much more effecitve as the movie progressed. The film is very much self-referential in that regard, and so it makes sense that Parker, whose character acknowledges that most people blame him for Elvis’ death at such a young age, is given the task of narrating the film: he’s a promoter, and the film is a (loving, its true) promotion of Elvis the Celebrity.

After opening with Parker’s heart attack, it switches to a montage of him wandering through a Vegas casino, talking directly to the audience briefly before moving on, not to Elvis’s early life, but to how Parker discovered him. We get a few flash backs of Elvis sneaking into black establishments to hear music, but little else of his childhood. I will return to this shortly.

The film only really kicks into gear when Parker becomes his manager, and Elvis becomes a star. From there, it recounts his early exploits as a teenage idol/slash public enemy, with his subversive sound and sexually suggestive dance moves leading Parker eventually to push him into the army, to avoid legal troubles in the segregationist South (or so it seems—Parker had his own reasons, as we find out). The death of his mother is treated swiftly and barely registered, while his film career is skimmed over when he comes back from Germany with his wife Priscilla in tow.

But Luhrmann’s style is much more effective in depicting the second act of Elvis’ career, dating from his 1968 Christmas special, when his life became the kind of circus that Luhrmann’s cinematic vision fits to a tee. In his vision, Elvis wants to join in the 1960s protest movement, and indeed he sings a protest song to end his Christmas special, as the first real conflict with Parker ensues. Elvis wants to tour abroad but is lured to Vegas by Parker who has gambling debts, and when he is finally ready to break free from him, his father Vernon reveals that they are badly in debt to Parker and out of money. Elvis remains in Vegas, and descends further into a drug fuelled death spiral.

The film ends with a montage of footage from the last performance he ever gave, in 1977, plus footage from his funeral. Parker, in a final voice over, claims that it was not drugs or fame or himself that caused Elvis’s early death, but instead it was “love,” his love for his audience that drove him to his premature demise. I’ll come back to this as well in a moment.

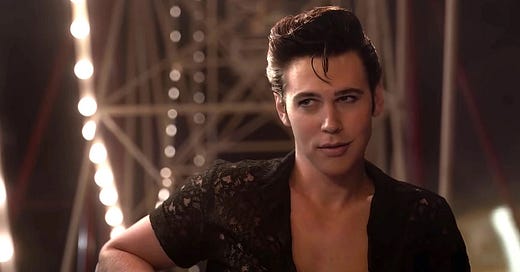

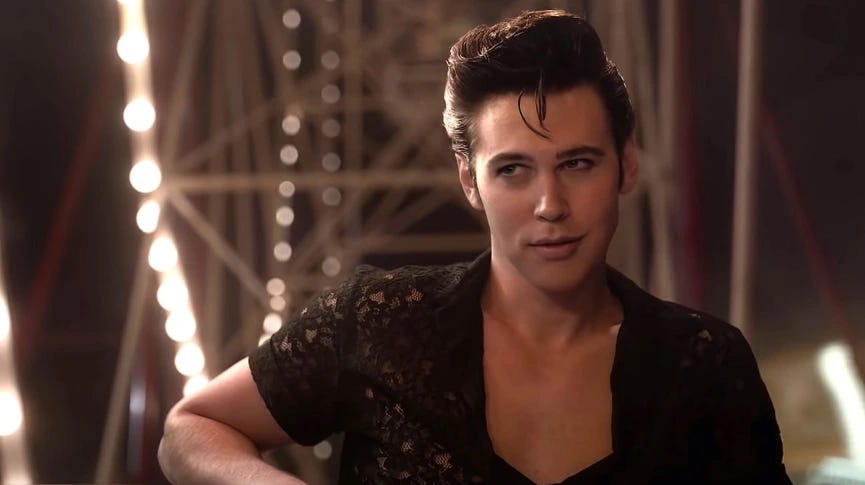

The strongest part of the film without question were the performances of the two lead actors, Austin Butler as Elvis and Tom Hanks as Parker. Butler is completely new to me, but his performance is stunning. He looks like Elvis generally, but he captured his voice almost completely. From what I understand, he also sang the vocals for much of the film’s music and was phenomenal. The way he channeled the energy that Elvis put out on stage, whether as a young man or as the older Vegas entertainer, is simply amazing. His performance alone is worth watching the film. And I think I liked Hanks better in this role than any other he has done, just because he was playing such a sleazy character, and still brought his native likeability to the part. The performances were great across the board, but I would also single out Olivia de Jonge, another performer I am not familiar with, who gave a very sympathetic portrayal of Priscilla Presley, one that added to the pathos of Elvis’s decline.

Though I enjoyed the film, and definitely recommend it, there are still a couple of things that bother me about it on reflection. Luhrmann should be commended for not doing another by the numbers biopic, and giving a style that fit the narrative he wanted to create. But it does seem to me he short changed Elvis’s early life for his later career. I can see why he did that but we don’t really get to learn about his upbringing, and his relationship with his mother is treated more briefly than you’d expect in a two and a half hour film. The emphasis on Elvis’s later downfall is understanable but it does seem a bit superficial, a bit obsessed with celebrity rather than the man himself.

This is especially true with the resolution of the film, when Parker makes the claim that it wasn’t him or “dem pills” that led to his premature death, but rather his “love” for his audience: Elvis loved his adoring fans too much and overworked himself to death. I’m not sure if Luhrmann meant Parker to be taken ironically, but it didn’t seem like it. This is puzzling, as the film presents him as someone who clearly manipulated Elvis, emotionally and financially.

Despite this, the film seems hesistant to indict too Parker too harshly. Perhaps this is because he was played by Hanks, whom everyone loves, but I suspect this has something to with what is its basically culturally liberal view of Rock n’ Roll: he emphasizes Elvis’ relationship with B.B. King and black people more generally, lauding the young as Elvis as rebel against the segregationist South, and later as an admirer of Martin Luther King Jr. and Bobby Kennedy. Notably absent from the film is any real consideration of class: Elvis the subversive celebrity is lauded, but the poor white kid from rural Mississippi barely makes an appearance. His early life is treated only in passing and then only to set up his character as a rebel held in check by a bad old white man.

But Rock was subversive of other things as well. When we first encounter Elvis, we see an almost lustful Parker slobbering over the effect Elvis has on young girls. By monetizing Elvis’s breaking down of sexual taboos, he knew he could make a fortune. As Parker puts it in one scene, “I wanted to find someone who could make people feel something they weren’t sure they were supposed to feel.” Parker repeats this phrase when gazing upon the reaction of a teenage girl to Elvis, and it is not exactly clear, but it gave me the impression that Luhrmann’s thinks this subversion of puritanical sexual norms is commendable, as if they were the analogue to the racist segregation laws of the South. Later in the film, when Elvis is under fire because of the sexuality of his performances, he laments to Parker that the phrase “Elvis the Pelvis,” the term the press came up with to denigrate him, “is a childish thing for an adult to say.” Which is true, but then Elvis shoved his crotch into the face of teenage girls on stage, which is not exactly adult behavior. Elvis was probably as innocent of the import of his performances given his background, but the verdict of the filmmaker seems to be that this was a Good Thing and only bad racist prudes could think otherwise.

The problem I have with this—and something in his direction makes me think perhaps Luhrmann understood this implicitly—is that the breaking down of inhibitions is precisely what sexual abusers attempt to do to their victims: gain their trust, get them “to feel things they perhaps shouldn’t feel” and then force them to do things they wouldn’t otherwise do. The film dwells on Parker’s manipulation of Elvis but doesn’t seem to make the same connection with how Parker (and by extension, the popular music industry) manipulated its audience through sexual suggetion. I’m guessing this is because Luhrmann sees the Sexual Revolution as unproblematic. Apparently, getting a cultural liberal to see the connection between the general breakdown of sexual mores and the proliferation of sexual abuse is well nigh impossible. This might explain why Parker is portrayed relatively favorably, despite the fact that he sounds like a creepy old pervert at times. That the music industry is notorious for taking advantage of young stars in more ways than one (as is Hollywood, of course), only adds to this impression.

Perhaps this is why, even though Luhrmann acknowledges Elvis’s innocence, he can’t really portray how badly he was abused, since that would mean damning the rock star celebrity cult he clearly wants to celebrate. Elvis is a tragic figure not because he loved his fans so much, but because he was such an obviously decent person whom the music industry chewed up and spit out, someone who loved music but clearly didn’t need the rest of the bullshit that goes along with being a rock star. One gets the impression he would have been happier, and lived longer, if he had only been a minor figure, producing music he liked, rather than being turned into an entire industry by his manager, and a cultural icon by everyone else. But then if he hadn’t, there would be no film for Luhrmann to make, would there?