I

When was a boy, my parents bought a collectors set of Time-Life books called The Old West. They still have them, but I had not given them a thought in years until I planned this trip to Dodge City, Kansas. Those Time-Life books are a relic of the Before Times, when there was no Internet, and you had to buy books or rent them from the local library to research your subject. There is no cost to such now, as you can find as much knowledge or pseudo-knowledge as you can stomach at your fingertips. I thought about those books, where I learned then names of men like John Wesley Hardin, Bill Longley, and other more obscure figures alongside more famous names such as Billy the Kid, Butch Cassidy, and of course, Wyatt Earp.

My graduate work in history was in British history, and I had not given much thought to the history of my own country until obliged to teach survey courses in that subject. But the past several years, as I have come to abandon my academic aspirations, my thoughts have turned more and more to American history. Moreover, subsumed with academic preoccupations, I ignored all the history nearby in the Midwest where I have lived for almost two decades. So for the past few years, I have been trying to visit any interesting places within a few hours drive of where I live, to try and inhabit the place that I lived in more intentionally.

Dodge City came to mind not because of those old books, long forgotten, but because an email from a travel blog suggesting interesting places to visit in the Midwest brought it to my attention. The scene of the great cattle drives, the Earp brother, Bat Masterson, and other highlights made it an easy choice.

I planned my trip to coincide with Dodge City Days, the yearly celebration the town puts on every year, thinking I might partake of some of these celebrations. As it turns out, I did not, but the trip did not disappoint for all that. I am not sure what I expected to see there, really. Perhaps it was just a case of curiosity gone mad, by someone who needs something to look forward to on a daily basis. But just because you cannot describe your goals in minute detail, does not mean they do not exist. Sometimes you have to find out by reaching for them.

So, I made reservations for a hotel—Hotel Wyatt Earp, to be exact—for July 28 to August 1, and prepared a list of things I wanted to see. These included

The Boothill Museum (dedicated to the town’s history);

the Coronado Cross, which marks the passage of Francisco Coronado through the area just south of Dodge City;

Fort Dodge, an Indian fort meant to protect settlers, which was once commanded by Custer;

And an excursion two hours north to visit the Jersualem Badlands State Park, for an entirely different kind of historical experience.

Beyond that, I planned to play things by ear, and let the day take me where it would.

II

By the morning of the 28th, I packed up with my Yorkie in tow, and made for Western Kansas. The Great Prairie Desert isn’t quite as barren as you would imagine, at least until you reach the center of the state driving on I-70. The road to Dodge from Kansas City goes through I-35 South to US 50, a good five hour trip that takes you through Emporia and bypasses Wichita to the south, the last major population center in the state. On this route you traverse a steady series of Kansas Ag towns along the way-Newton, Hutchinson, and more than a half dozen others-whose landscape alters the further you drive west, some so flat and treeless you can see the entire town from the highway.

These small outposts are built around farming and family. Every one of them contains at least two features: a feed yard, and at least one church (often more than that). Passing through the main streets of these towns, I turned my head to what their homes looked like, what type of people live in these isolated towns. I noticed on some their front yards were signed planted, expressing support for an amendment to the state constitution that was voted on a few days later in August, restricting access to abortion in this state. (It did not pass.) Where I live outside Kansas City, most of the signs I saw were opposed to the amendment, but nearly everyone I saw in Western Kansas supported it (except for one-in Dodge City as it turns out).

When I first came to Kansas for graduate school, I went to lunch with some new grad students in my department. I can’t remember the tenor of the conversation, but somehow it came around to Western Kansas, and one of them (they were all women), made a remark whose details escape me but whose upshot was “I would never go out there! Those people frighten me!” I said nothing, since I had never been there, but felt instinctively this was nothing more than snobbery. During my introduction to the department I taught in, I was required attend training sessions to familiarize myself with the program. I recall at one of those meetings being warned that my students were aggressive fundamentalists, and in so many words, bigots, with whom I should not back down from if challenged in class.

I mention these memories because such talk was nothing more than snobbery and prejudice. My students were unfailingly polite, and decent, and the only encounter I ever had with a “fundamentalist” was a student who admitted in class she did not believe in evolution but wrote an excellent essay about why she did not. She received “A” in my class. Over time I made several friends from Western Kansas, and I have never known them to be anything but kind, wonderful human beings.

I suppose it was the people, as much as its history, which compelled me to get into Dodge.

III

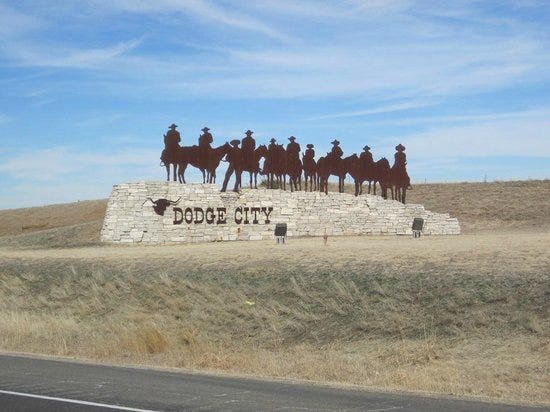

The weather turned cool and rainy as I made for the road that day, a welcome change from the normal inferno of a Kansas summer. The sky was overcast as I turned from the highway onto Wyatt Earp Boulevard, the name for the main strip running through Dodge City. You can tell it differs from the numerous towns that surround it the moment you approach, because there is a large sign with cowboys in silhouhette that greets you across from the feedlot overlook.

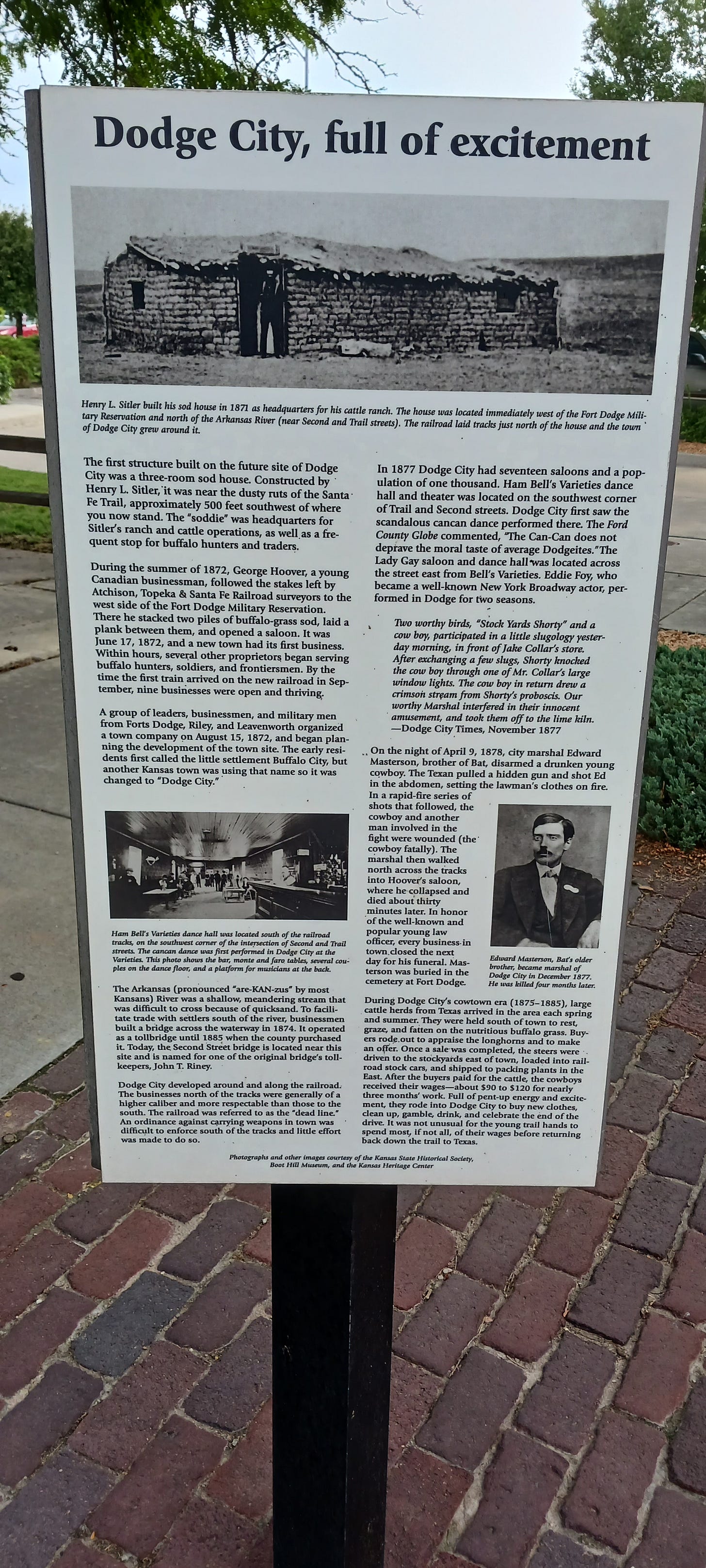

The first thing you notice about Dodge City is the lay of the land. Dodge City is built upon a slowly rising ridge that overlooks the plain below, and Wyatt Earp boulevard is at the bottom, where much of the business activity takes place in the city. Like pretty much every American city, it is a series of auto shops, strip malls, restaurants (lots of Mexican restaurants, as we will see), McDonald’s, Burger Kings and the like. But further west you hit the center of the town that was founded in 1872 and became as a stop on the cattle drives heading north for the meat packing plants of Chicago and the East Coast. On the south side of the boulevard is the old Santa Fe train depot, which has been turned into a dinner theater, and further down the street is what I came for: Front Street, the main street of the town where gamblers, gunfighters and lawmen clashed during those days of the cattle drives.

Just west of front street is the Boothill Museum, which, as we will see, was named for the cemetery established on the hill overlooking the town, where many early victims of the town’s gunfighting were buried “with their boots on.”

My hotel lay on the western end of Wyatt Earp Boulevard, heading out of town. Naturally, it was The Wyatt Earp Hotel.

The place seemed a bit sketchy to me, as you didn’t need your card key to get into the building, and I worried about someone stealing my dog while I was out exploring the city. But it seemed well run enough, and was definitely cheap for a four day stay.

One aspect of travel in America that I am sure everyone has experienced is going through small towns and passing signs that announce the presence of an “historic district.” I always wonder about these, since mostly they just refer to some old building, without really explaining why they are important historically. Mostly, they are just a Chamber of Commerce attempt to promote the city, but the thing about Dodge City is that its denizens clearly understand the value of its historical reputation. It actually owes its Old West reputation as much to the Eastern press of the 1870s as to its very real penchant for violence. Myth and reality merge in a place like Dodge City, in a very peculiar way.

I noticed right away that the neighborhood around my hotel was populated by people of Mexican descent or mixed Anglo-Hispanic descent. According to the Census Bureau, 79% of the population of Dodge City is classified as “white” but of these some 63% are also “Hispanic.” In other words, a large part of the 27,000 or so citizens of Dodge are mixed race. It was not a coincidence that Wyatt Earp boulevard is dotted with hole-in-the-wall Mexican restaurants (which were great—I should have eaten at more of them when I was there). At the bottom of the ridge that dominates Dodge City are the working class, lower income population. But as you go up the hill and father north, toward the community college, the high schools, away from the historic center and out to the suburbs, the houses get bigger and newer, though if my perception correct, not necessarily more “white.” In other words, the geography of Dodge City is encoded by class. And as I was to find out, it always has been.

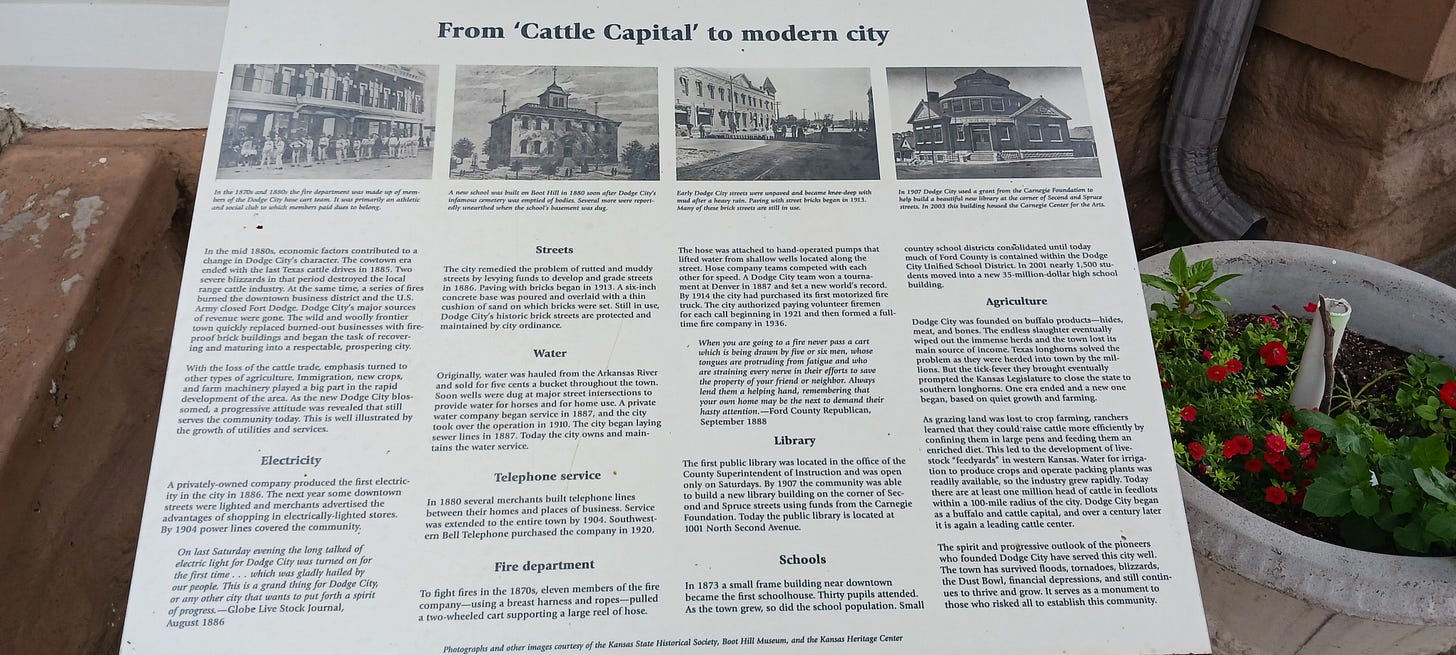

IV

After I settled in at my hotel, I left Gus (that’s my Yorkie) and took a quick trip down to Front Street, to walk around and see what “historic” sites remained in the historic district. Not much from the Old West, to be sure. Fires burnt parts of the city during the 1880s, following the end of the cattle drives (caused by disease), and Dodge settled down into becoming an agricultural town. (It should go without saying that this means Big Agriculture, not small farmers: on the way in I saw a fertilizer plant run by Koch Industries—yes, that Koch Industries). I did find some sites from a later age, however, revealing a bit about how Dodge changed after its Old West heyday.

You can find old Carnegie Libraries all over the place from the early twentieth century, the result of Carnegie foundation grants. (There is one in Eureka Springs, Arkansas, a place I have been to several times.) The historical marker in front of the arts center proudly explains that the city revealed its “progressive” attitude in the years after the end of the cattle drive. It was not the only sign of “progressive” ideals in the city, as Dodge City boasts a “Teachers Hall of Fame,” which claims to be the first one of its kind in the nation.

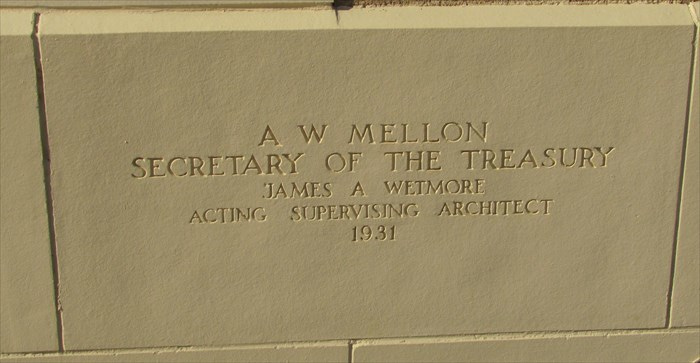

On my walk through the city center I saw a fine looking building that I thought might be in the New Deal style, which turned out to be the town post office:

In the event I was mistaken, as the building was not old enough to have been built by Franklin Roosevelt’s alphabet soup of works programs (they date from 1933 and 1934), though I still think it bears a resemblance to the many post offices build under his auspices.

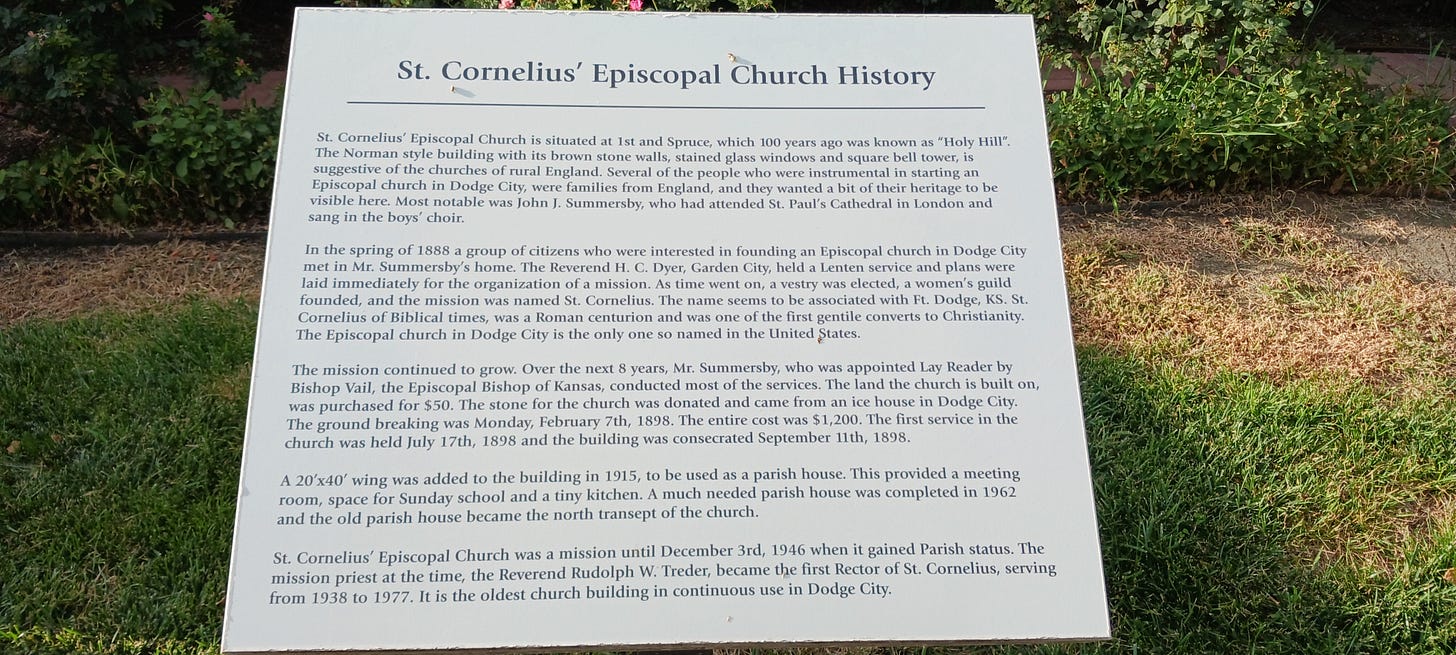

My tour of “old” Dodge City took me to what is sometimes referred to as the “Holy Hill,” a collections of old churches on the east side of the city near Central Avenue, starting with St. Cornelius Episcopal Church on Second and Spruce.

A few blocks east and you come to First Presbyterian on Central Avenue:

And just up the block, the former Catholic Cathedral of Dodge City, Sacred Heart. Built in 1916, it is now an official city landmark.

The city has an interesting religious history, as it is a mixture of Protestant churches but also a Catholic presence earlier than the town itself. The Osage Mission in St. Paul Kansas began serving US soldiers along the Santa Fe trail well before Dodge was established, and in 1869 a Jesuit named Phillip Colleton established a mission for railroad workers in the area around what would become Dodge City. In 1882, Sacred Heart parish was established as the first Catholic Church in the city.

The Catholics in Dodge were originally served by a mission from the church in Windhorst, Kansas, something I mention because it will become part of my journey here in Western Kansas. But also because it illustrates the precariousness of how this place was settled. Windhorst was founded before Dodge but eventually disappeared when the Santa Fe Railroad bypassed it. There is a phenomenon here in Kansas of ghost towns, which cease to exist for one reason or another, and illustrates that it took personal risk to settle this place.

It also hints at how Dodge City has remained where other towns have not. In the 1930s, Hollywood made a film about the city starring Errol Flynn, and of course for many years the television show Gunsmoke portrayed the town’s “Wild West” past on the small screen. This is all the more notable in that the town’s aura rests mainly on the days of the cattle drive, which only lasted ten years (1875-1885). Dodge City has survived, in part, by making astute use of its history and reputation, to remain not only a thriving but a place with a claim on the American historical imagination. This is no mean achievement, and the evidence of it is all around you when visit its “historic” city center:

I eventually made it back to the Wyatt Earp Hotel before it began to rain, as you can see from this last picture. I had to do some grading for my remote classes (the perils of an adjunct’s life) before I turned in for the evening. The hotel room’s interior was actually much nicer than I expected, and I generally slept well there. But I had been obsessively checking the weather and knew it was going to rain pretty much all the next day, which it did. The deluge began just after I arrived back at the hotel, and as I tapped away at my computer I wondered how long it would last and if it would ruin the rest of my trip. As it happens, for the better part of two days it cooled things off, and made the trip a unique one during the normally the dusty dry summer days of Western Kansas. At the time it seemed to threaten my plans, but that is the joy of travel isn’t it—if we are fortunate, unexpected difficulties sometimes turn into unexpected delights, the kind that make like worth living.