The following is an article I submitted for publication and could not find any takers for (to be fair, I only tried one, but I don’t feel like shopping it that much). So, since my newsletter is dedicated to literature, among other things, I hereby present it to my readers. I hope you enjoy it. —Darrick

The subject of technology and its affect on our lives is on the lips of our social commentators everywhere these days, and for good reason. First, it was the television that provided grist for the mill of those like T.S. Eliot who thought it heralded the doom of civilization. His warnings seem quaint in the age of the Internet, as the speed and compulsiveness of digital “social media” has increased exponentially from Facebook to Twitter and now Tik Tok, which is apparently the main source of knowledge and entertainment of younger people today (or so my nephew tells me). The coming of Artificial Intelligence only promises even greater acceleration of the curated, virtual world that constitutes so much of our public and private life.

How can someone cope with this electronic simulacrum of life we have created? I am not one to downplay the very real and unprecedented challenges that our current present us with. One of the major challenges of human life, both morally and intellectually, is learning to tell what is real from what is counterfeit. This is the primary threat that Artificial Intelligence poses to us; in one case, enterprising criminals have already made use of its ability to imitate patterns of human speech to extort money from parents, imitating the voices of their children and pretending they had kidnapped them.

But the issue is one that has arisen before in history. Before the Digital Revolution, there was the Print Revolution of the early modern era, and all of its attendant transformation of Western Society. Print made possible the Protestant Reformation and the emergence of modern public opinion, and the press was so destabilizing of early modern governments that its products--mostly pamphlets--were dubbed “paper bullets.” With the development of new media of communication came a new form of art that mediated “reality” to early modern peoples much the same way Tik Tok does for Zoomers. That art form was the novel, of course, and though it conquered the Western mind as the preferred vehicle for its self image, at least one critic understood its limitations from the beginning.

The Clergyman Auteur

The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman, was an eighteenth century bestseller, published in nine volumes between 1759 and 1767 by its author, Laurence Sterne (1713-1768). His literary creation made him the talk of London and he was feted as a great author. Sterne’s contribution to literature is unique in several ways; Tristram Shandy is often credited with originating a writing style that is the progenitor of modern fiction techniques, such as stream of consciousness writing. Another is that he was also an Anglican clergyman.

Born in Ireland of a English soldier from the north of England, he grew up in Halifax in Yorkshire, before moving on to Cambridge. Sterne entered the Anglican ministry shortly after graduating, and becoming a successful clergyman, gaining a post at York Minister, where his sermons were quite popular (he published several volumes of these in his lifetime). For a brief time in the 1740s, he wrote pamphlets in favor of Sir Robert Walpole’s government but quickly ceased, finding politics a dirty business (but incurring the enmity of an uncle who had been his patron). He fell in love with and married Elizabeth Lumley in 1741, sharing a somewhat unhappy marriage with her, partly due to his infidelities.

In 1759, he discovered his true metier when he published a satire on the upper clergy entitled A Political Romance, which so infuriated the grandees of the Church of England that they burnt it. This effectively ended his ecclesiastical career, and began his writing career. The same year, he published the first two volume of Tristram Shandy at his own expense, even as he suffered the deaths of his uncle and his mother, as well as the nervous breakdown of his wife. When the book hit the London scene in 1760, it became a runaway success.

Sterne spent the remainder of his life writing from his home in Coxwold, between bouts of being feted in London. He did manage to escape the continent for health reasons in 1762, which provided material for his A Sentimental Journey, appearing in 1767, the same year as the final volume of Tristram Shandy. A year later, Stern succumbed to the tuberculosis he had suffered from since his days at Cambridge in 1768.

The Christian Seinfeld

Why am I talking about Tristram Shandy, a work that Samuel Johnson once wrote of that “nothing odd will do long. Tristram Shandy did not last”? It is a fair question, because, despite its title, Sterne’s masterpiece never quite gets around to relaying the life or the opinions of its main character. In fact, Tristram is not born until the third volume of the work, and as the work ends, it is still recounting the efforts of his uncle, suitably named Yorick, to woo the “Widow Wadman.” If the work never fulfills its promised end, it is because the narrator, the putative Tristram, keeps getting lost in digressions and off topic stories that take up most of the work.

Tristram Shandy is a novel, then, about nothing in particular, except the digressions of its author and the minutiae he shares willy-nilly with his readers, akin to an eighteenth century Seinfeld, the show famously “about nothing.” The reason for this illustrates the genius of Sterne.

As the novel begins, Tristram tells how he was conceived by his parents, but then to explain why the moment of his conception is important he tries to explain John Locke’s theory of the association of ideas, which leads him to his parents’ marriage contract, which leads him to his uncle Toby…you get the picture. In the middle of the fourth volume, Tristram realizes that he will never be able tell the story of his whole life, for it will take him longer to write it than to live it. As he puts it in the fourth volume, by that point he gone “no farther than my first day’s life” in the telling, and after a year of writing he is “thrown so many volumes back” than where he was the year before.

Sterne’s achievement was to spin a delightfully self-defeating narrative that calls attention to its own artificiality and inability to capture “real life.” For instance, Sterne consistently “breaks the fourth wall” by speaking directly, not only to his readers but to his critics. At one point, the Tristram/Sterne narrator compares “a man’s body and his mind” to a “jerkin, and a jerkin’s lining,” and chides his critics in this vein: “You Messers. The monthly Reviewers!----how could you cut and slash my jerkin as you did!----how did you know, but you would cut my lining too?”

This is standard enough fare, but Sterne goes beyond this by toying with the conventions of print in myriad ways, some subtle, some not so subtle. For example, when he narrated the death of his uncle Toby, Tristram/Sterne made the two following pages black:

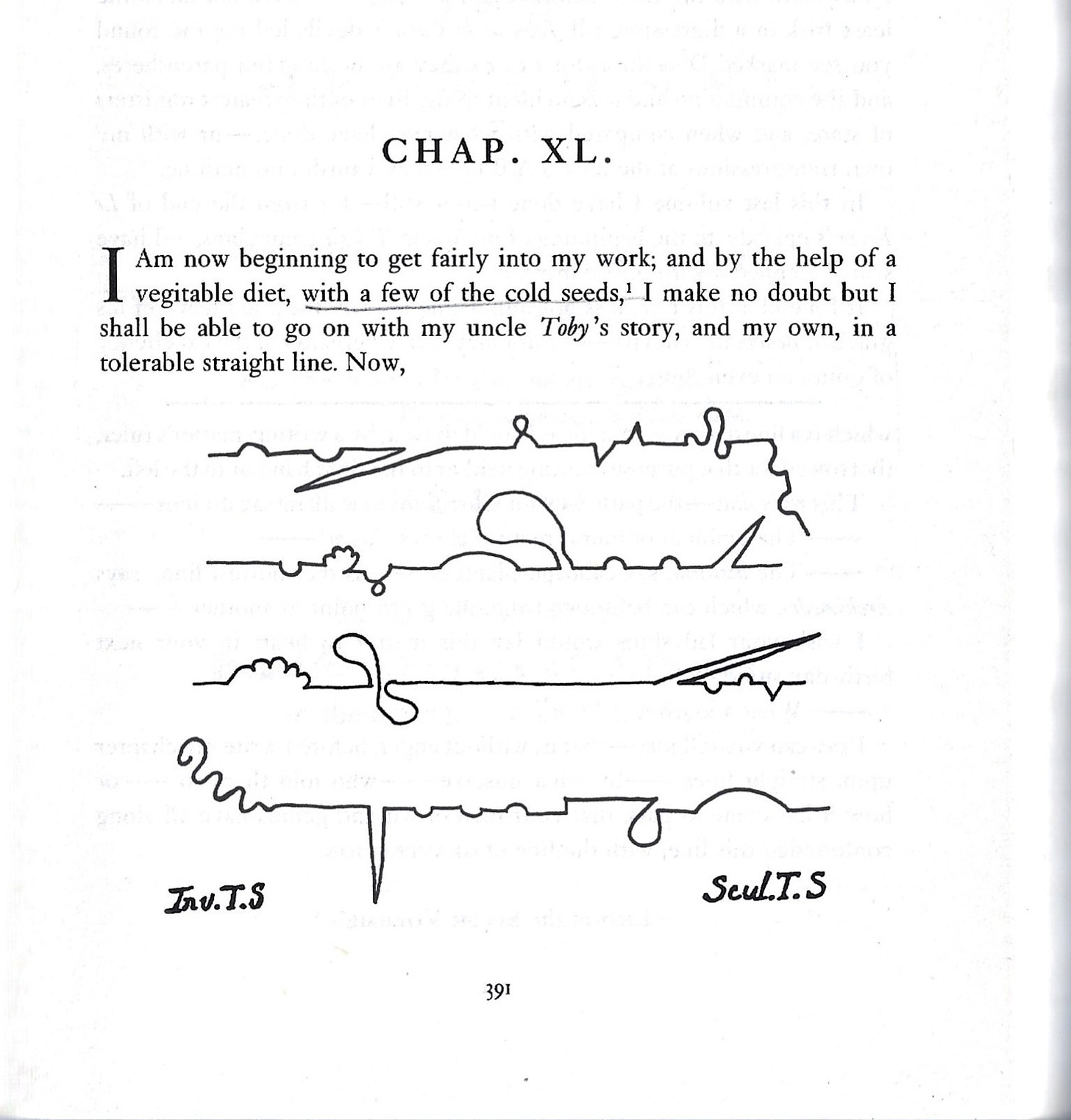

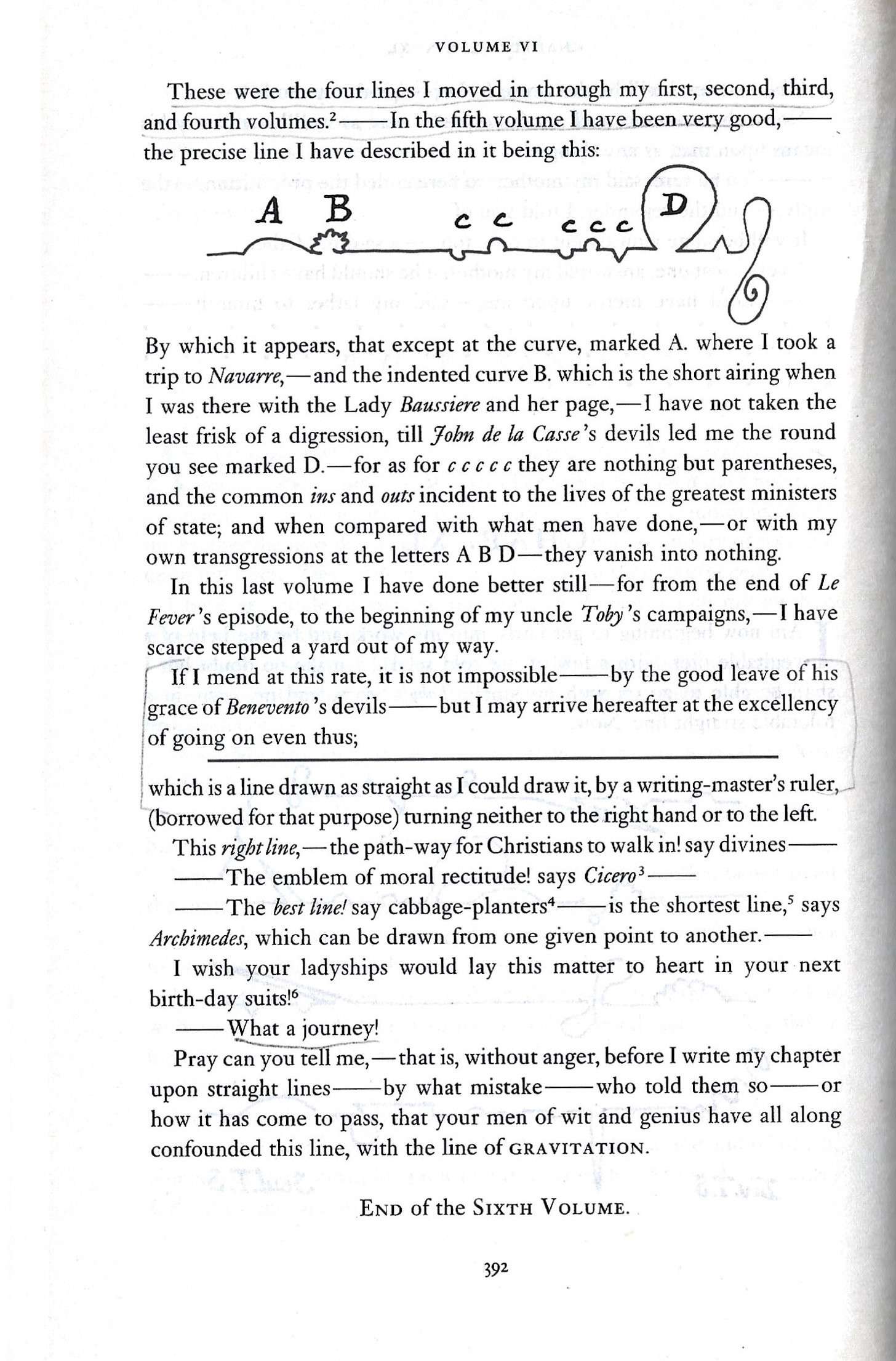

Sterne used the visual aspects of print to his advantage in other ways. At the end of the sixth volume, he draws attention to the fact that Tristram Shandy does not follow the linear, successive tale expected of early novels with an illustration:

What Sterne is doing in these passages is pointing out how the physical artifact of the printed book creates the illusion of direct access to “reality,” by directing the reader’s attention back towards what the reader normally wants to forget, the artifice of the novel itself. For that is what the “realist” genre of the novel purports to do--to capture reality. Sterne was not the first eighteenth century novelist to do this--he is, as many scholars rightly point out, deeply indebted to Jonathan Swift--but he is unique in the way he does this.

In this regard, Sterne is doing something similar to what his Irish descendant Oscar Wilde does in The Decay of Lying. In that dialogue, one of the characters blames the prevalence of fog in London on certain English painters, who have taken to painting the city draped in fog. Wilde’s tongue in cheek assertion is meant to draw our attention to how narrative and other frames condition how we see the world. Tristram Shandy not only aims to tittle the reader by playing with the conventions of print but also to puncture modern pretensions to capture “the Real,” and make it subservient to the reader’s pleasure.

Print works as a cultural medium by disciplining the reader at a physical level, forcing the reader to scan lines in a mechanical, repetitious way. Sterne shrewdly understood that once you acquired this habit of reading words in a stable, uniform way, you can be fooled into thinking print has authoritatively described the world. And print in the eighteenth century certainly did have this effect. Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther is a prime example: the book influenced susceptible readers to commit suicide in imitation of the main character (young men were found, drowned in the river, with the book in their pockets), not unlike the inane “Tik Tok” challenges so popular today.

It is difficult to remember now, as the Tower of Babel that was print has been succeeded by the Strife of Tongues our of digital media, but for a brief moment, no more than century, if that, the print medium seemed to give a stability to public life. In the form of newspapers, its long grey columns acted as the foundation stones of the “Fourth Estate” of modern democratic societies. This illusion began to break down with the invention of the steam press and other novelties in the nineteenth century, however. The hue and cry over the introduction of color photos in cheap newspapers during the 19th century must have been due to the worry it would spoil this illusion. But Sterne’s literary antics in Tristram Shandy were meant to call attention to the illusion quite consciously.

Sterne the Free Spirit

Modern thinkers like Friedrich Nietzsche and James Joyce have seen in Sterne a kindred soul, a “free spirit” like them, someone unhindered by conventions. Postmodern literary critics have a field day with him as well, because he seems to undermine “metanarratives.” It is true that Stern puts a great stress on the limitations of human mind, and enjoys skewering those who pretend to knowledge and certainty they do not possess. A famous passage from Tistram Shandy is often invoked as evidence of his “modern” approach to the world:

We live amongst riddles and mysteries--the most obvious things, which come in our way, have dark sides, which the quickest sight cannot penetrate into; and even the most clearest and exalted understandings among us find ourselves puzzled and at a loss in almost every cranny of nature’s works.

The number of revered modern novelists who trace their lineage to Sterne is quite impressive. Besides Joyce, authors as diverse as Goethe, Salman Rushdie, Thomas Mann and Carlos Fuentes all claim to be spiritual heirs of the eighteenth century Anglo-Irishman. If one wanted to make of Sterne a postmodern skeptic, there is material enough in his novel to fashion such an image: double entendres, bawdy puns, and other faux pas against standard literary taste dot the landscape of Tristram Shandy, something for which the more censorious among contemporaries criticized him.

The Anglican Erasmus

Such an image would be a chimera, however, for the reality that he was an Anglican clergyman was most important thing about Sterne. The editor of the Penguin edition of Tristram Shandy, Melvyn New has pointed out that the quotation above, so beloved by postmodern critics, occurs in a similar wording twice in Sterne’s sermons, where it refers not to the opacity of truth but to “a commonplace Christian belief in the limitations of the postlapsarian human mind.” The sentiments voiced in that passage go back to John Locke and behind him to St. Paul, in First Corinthians, who in the thirteenth chapter of that letter says “now we see through a glass darkly.” The source of Sterne’s skepticism about what print and the novel can accomplish is not postmodern unbelief but a sort of Erasmian or Rabelaisian Christianity, one filled with sheer delight by the limitations and therefore the folly of the human condition.

Erasmian style Christianity is sometimes accused of tending toward superficiality, a charge that was also hurled at Sterne during his lifetime. It is true that a sort of jolly attitude will only get you so far in life, and that at its worst, such a Christian mentality fails to take seriously the tragic element in human affairs. Sterne, however, never really falls into this trap, because he steadfastly refuses to take himself seriously enough to be superficial.

His faith and his realism are best illustrated by the way he faced his own mortality. Sterne’s tuberculosis meant he had to face the possibility of death from an early age, and as he completed the final volume of Tristram Shandy, he was aware that his end was near. A few weeks before his death in 1768, Sterne wrote in a letter that “I brave evils--et quand Je serais mort, on mettra mon nom dans le listes de ces Heros, qui sont Mort en plaisantant (and when I shall have died, my name will be placed in the list of those heroes who died in jest).”

Tristram Shandy is therefore more like a Praise of Folly for the age of print, than a Finnegan’s Wake avant la lettre. Sterne very much was a man of his time in terms of his learning, his main influences being Swift and Locke, as well as the general tenor of the eighteenth century Church of England. But he represents a permanent type, the Christian who finds the ways of the world false but inexhaustibly funny. Sterne possessed a faith in the Real that allowed him encounter the absurdity and topsy-turvydom of this world with equanimity and good cheer. Despite the manifold possibilities of the novel (which he exploited to the full), he understood that no literary innovation or technological advance could eliminate the enduring folly of human life. Sterne did not succumb to the artifice of print because he knew the larger pattern of the Real has been imprinted on the human heart.

Sterne and the Narrative of Techno-(dys)topia

Reading Sterne can remind us to look for those limits in technologies that tend to frighten us with their apparently unlimited capabilities. Those limits usually have to do with the fact that, while the technology we create can indeed imitate a part of our humanity, it cannot reproduce the whole of it. Such is the case with our voice patterns, as noted in the attempted extortion case above, or with algorithms, which can correctly identify shopping choices based on our past behavior (though not always with complete accuracy). This is the case with the most feared of our potentially “doomsday” technologies, artificial intelligence. The philosopher Edward Feser, reviewing the book The AI Delusion by Gary Smith in City Journal, cited the example of facial recognition software to make this point. Feser wrote that

image-recognition software is sensitive to fine-grained details of colors, shapes, and other features recurring in large samples of photos of various objects: faces, animals, vehicles, and so on. Yet it never sees something as a face, for example, because it lacks the concept of a face. It merely registers the presence or absence of certain statistically common elements…

…Software is not doing the same kind of thing we do when weperceive objects. The software doesn’t grasp an image as a whole or conceptualize its object but merely responds to certain pixel arrangements. A human being, by contrast, perceives an image as a face—even when he can’t make out individual pixels.

Sterne gloried in the possibilities of the printed page and the vehicle that was the novel, because of all the possibilities for satire and amusement that it created. But because Sterne was also a clergyman, he understood much better than our current technocratic overlords our (and their) human limits. Christianity enjoins us to strive for perfection (“Be ye therefore perfect, as your father in Heaven is perfect”) while reminding us that we are Fallen,and can never achieve this on our own.

In a sense, what Sterne teaches is how our attention to our technology can help us see through the sorts of counterfeits it makes possible--and how we are deceived by them. Just as we rightly fear their perversion to horrible uses--one need only think of what a computer hacker could do with self-driving cars, already deployed on the streets of San Francisco--we can lose sight too easily of the distance between our machines and our human capabilities.

Sterne plays with this distance endlessly in Tristram Shandy, as when he marks a cross in the text (U) whenever a Catholic character crosses themselves, playing up the absurdity of trying to reproduce in written symbols the action of someone making the physical sign of the cross (Sterne was conventionally anti-Catholic, but not with much conviction). In focusing our attention on this distance (which our machines can never cross), we can fortify ourselves against the fatalism that sometimes accompanies the latest technological breakthroughs.

Sterne’s jolly skepticism is a good corrective to excessive pessimism regarding our increasingly tech driven world. He reminds of us our limits, and therefore the limits of our creations, which can only approximate, but never capture completely, the Real. This Erasmian enjoyment of human folly is not a replacement for a fully mature Christian faith, nor with a realism that is rightly concerned with the dangers of counterfeits. Still, such joyous appreciation of our frailty is a necessary, if not sufficient, condition of finding our way in our digitized world.

With characteristic playfulness, Sterne ends Tristram Shandy on a note of self effacing ribaldry, in which he suggests to his readers that they have been hoodwinked into reading a nine volume tale which is, quite simply, bologna:

L--d said my Mother. What is all this story about?----

A COCK and a BULL, said Yorick----And one of the best of its kind, I ever heard.

We can take from Sterne’s ingenious novel a similar reminder. When fear grips us that the latest technological prophecy will prove correct--that it will erase our free will and turn us into mindless automatons, or that our machines will somehow rise up to kill us all--Tristram Shandy gently elbows us in the ribs, and shows us that we have, as usual, been falling for a cock and bull story all along.

Hey Darrick,

As I've told you before, I enjoy your commentary and this is a really solid and topical piece. I would encourage you to keep submitting your commentary to periodicals, if not necessarily this specific piece. ~ Alex